June 12, 1908 - January 12, 1942

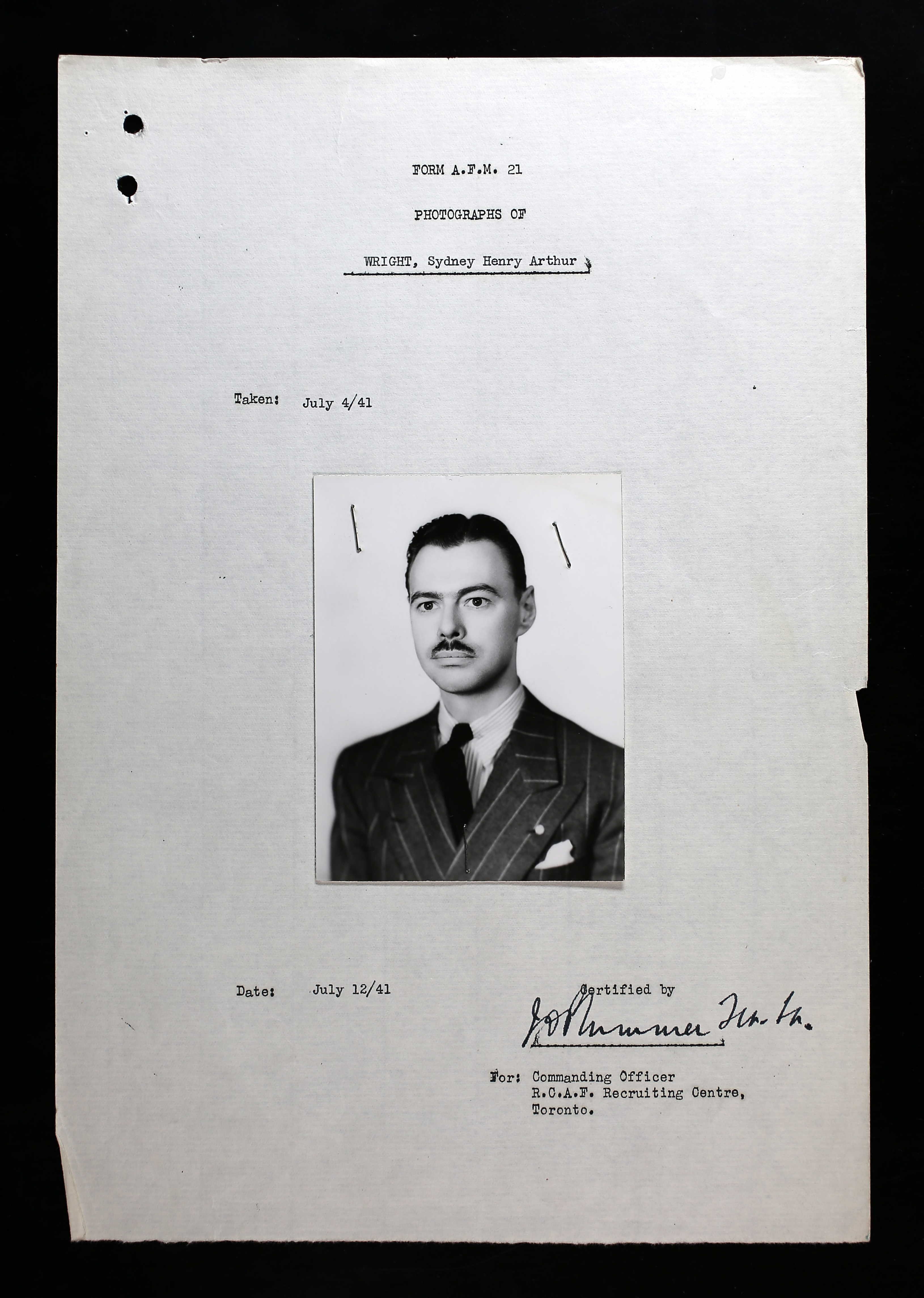

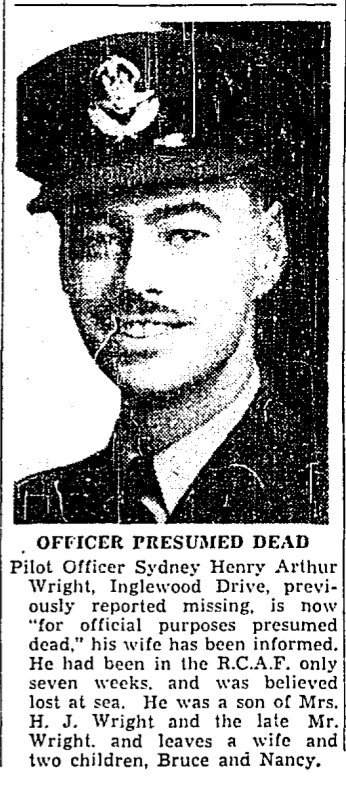

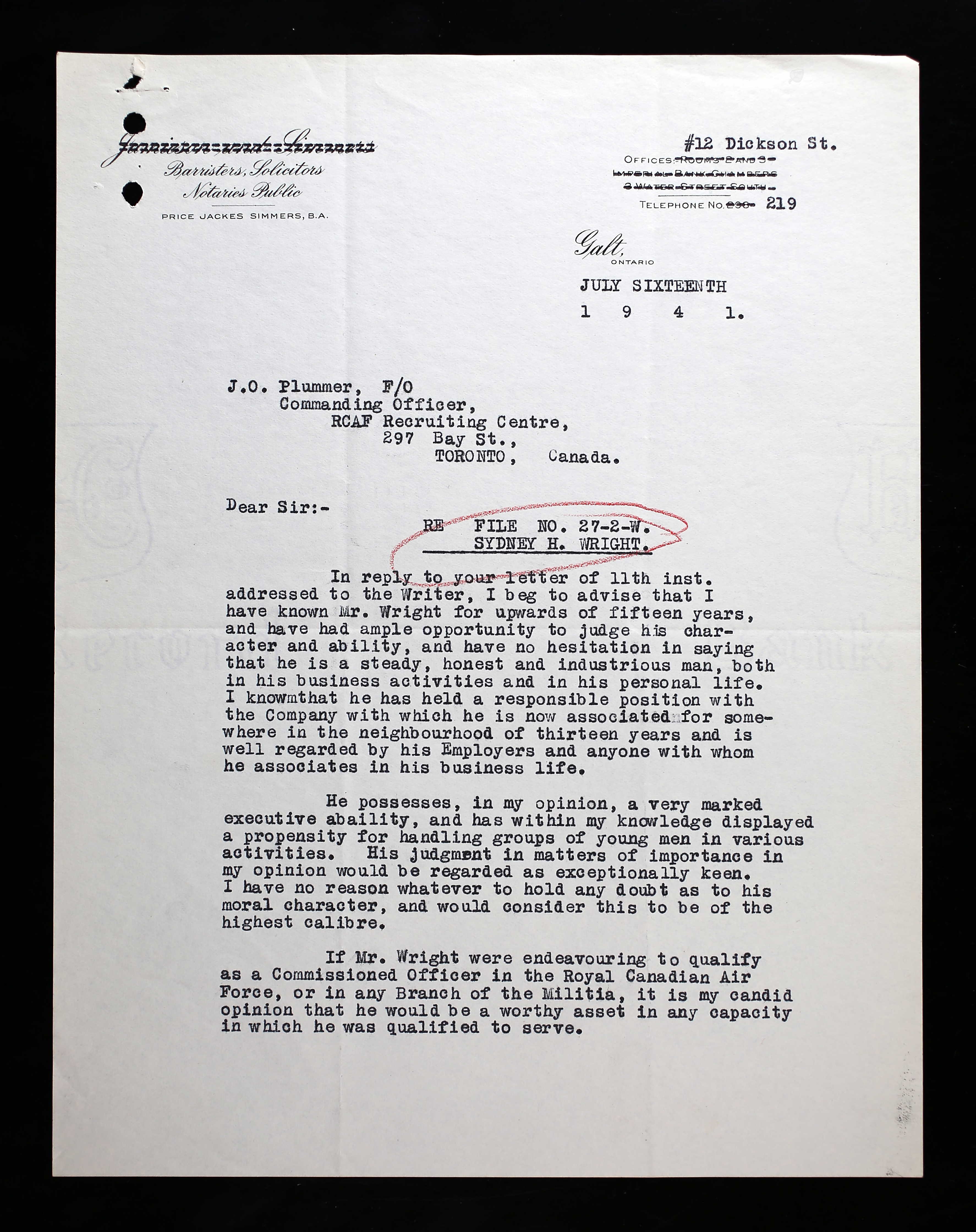

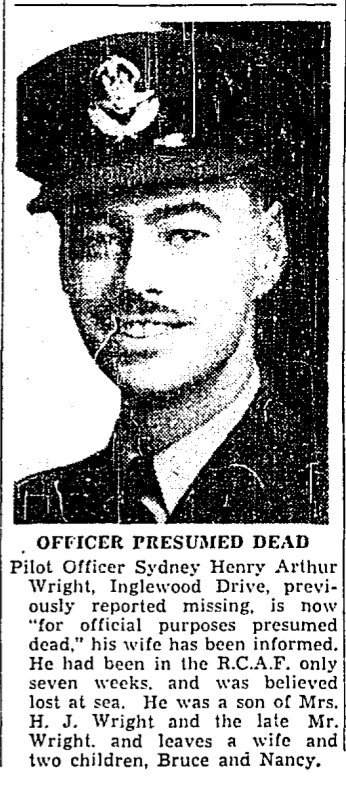

Sydney Henry Arthur Wright, born in Bromley, Kent, England, was the son of Henry John Wright (d. 1940), interior decorator, and Louisa Frances (nee Behets) Wright, of London, England, later of Toronto, Ontario, and the husband of Dorothy (nee Collard) Wright, of Toronto. He had one sister, Florence Mary Louise Simmers (1910-2004), of Galt, Ontario.

Sydney and Dorothy married on May 30, 1936 in Toronto. They had two children: Bruce Henry (b. May 17, 1937) and Nancy Ellen (b. May 23, 1941).

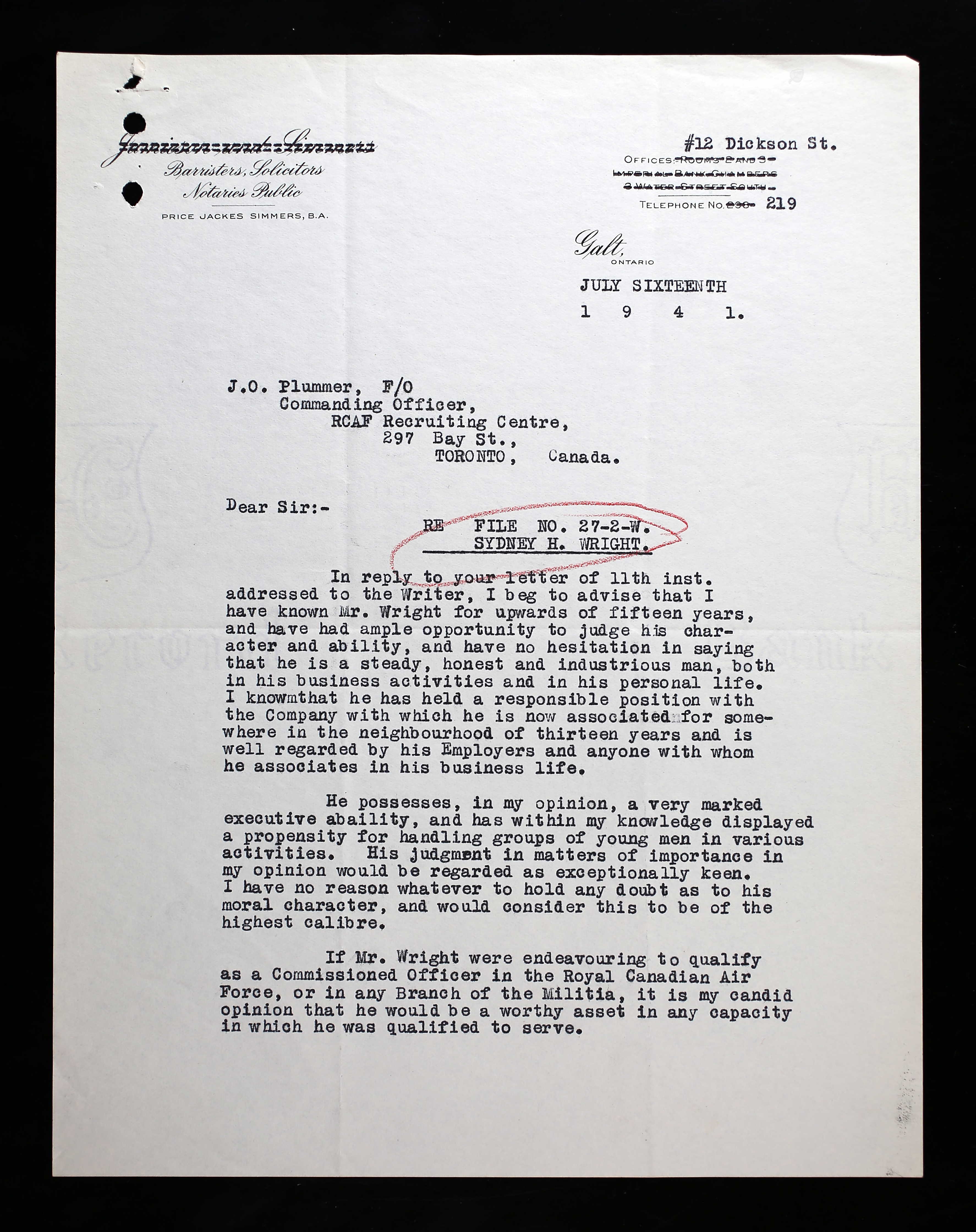

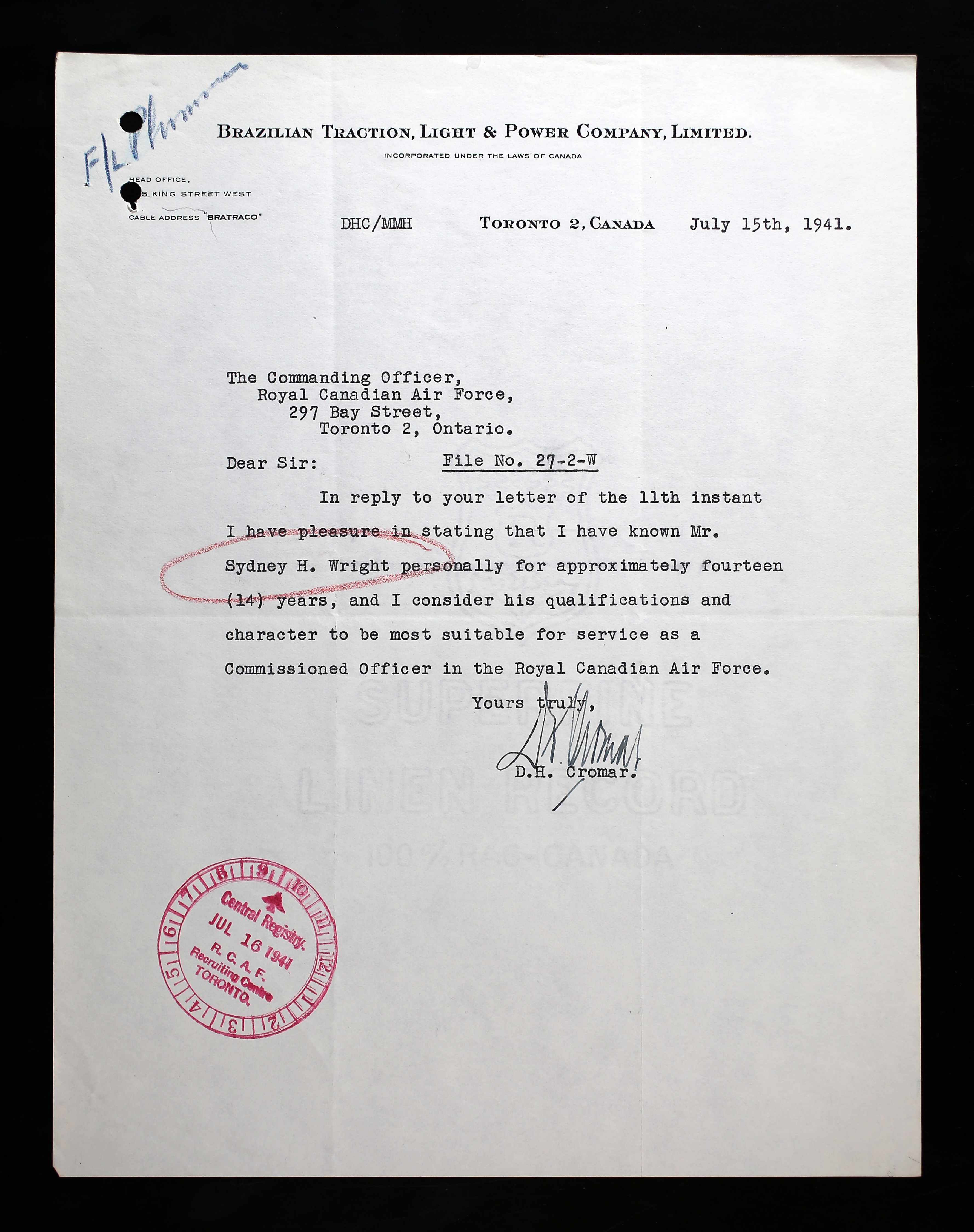

Sydney worked at the Dominion Bank of Canada from 1926-27 as a junior clerk and ledger keeper, then transferred to Brazilian Traction, Light & Power Company Ltd. until he enlisted with the RCAF in 1941. He worked preparing statements and entries plus did routine correspondence and accounting duties for them.

He was a member of the Toronto Ski Club, York Bible Class, Allen Club (public speaking and debating). He had previous military experience with the Corps of Guides, 1927-1928 as a sergeant and with the 2nd Divisional Signals RCCS (R) from 1928-1931 as a sergeant. He took three courses, one to qualify to be a sergeant, one on visual telegraphy, plus an additional course about line telegraphy.

Sydney felt that his general knowledge of basic principles of electricity and internal combustion engines would be an asset. he enjoyed skiing, camping, and canoeing. He also had a “better than average knowledge of aircraft construction from extensive reading of aviation magazines.”

He had $5.66 in a bank account as well as life insurance policies.

On Sydney’s Personal History Report by the Retail Credit Company, dated July 29, 1941: “Worth: $3,000. Annual income: $2400. Good reputation. Mr. Wright has a High School education at least and his school record is good. He has been with the present company since he was about 19 years of age and is in good standing with his employers. He started as an office boy. His parents are not known. The subject is married and lives with his wife and one child in a working class rented home. Home surroundings are desirable, and he is well regarded in the neighbourhood. His associates are a desirable type and loyal citizens. He has expressed himself as being pro-British. He is not active in civic, fraternal, or church organizations.”

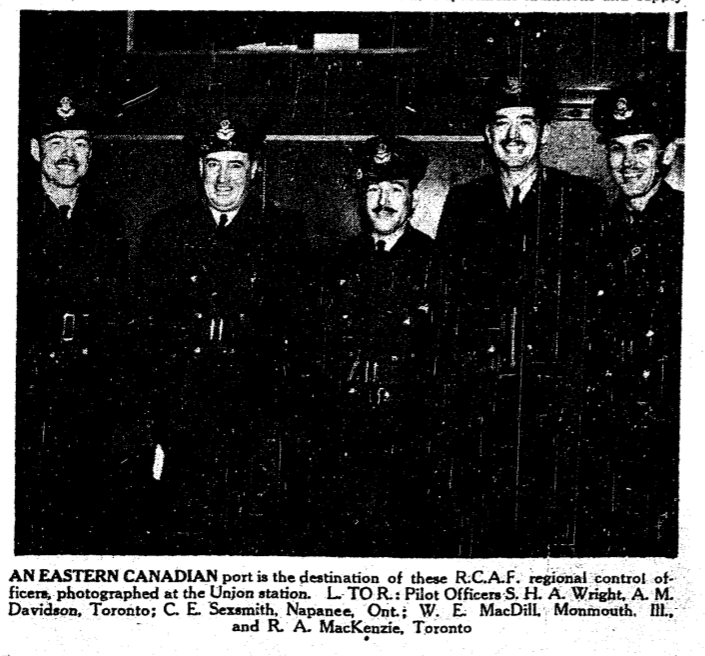

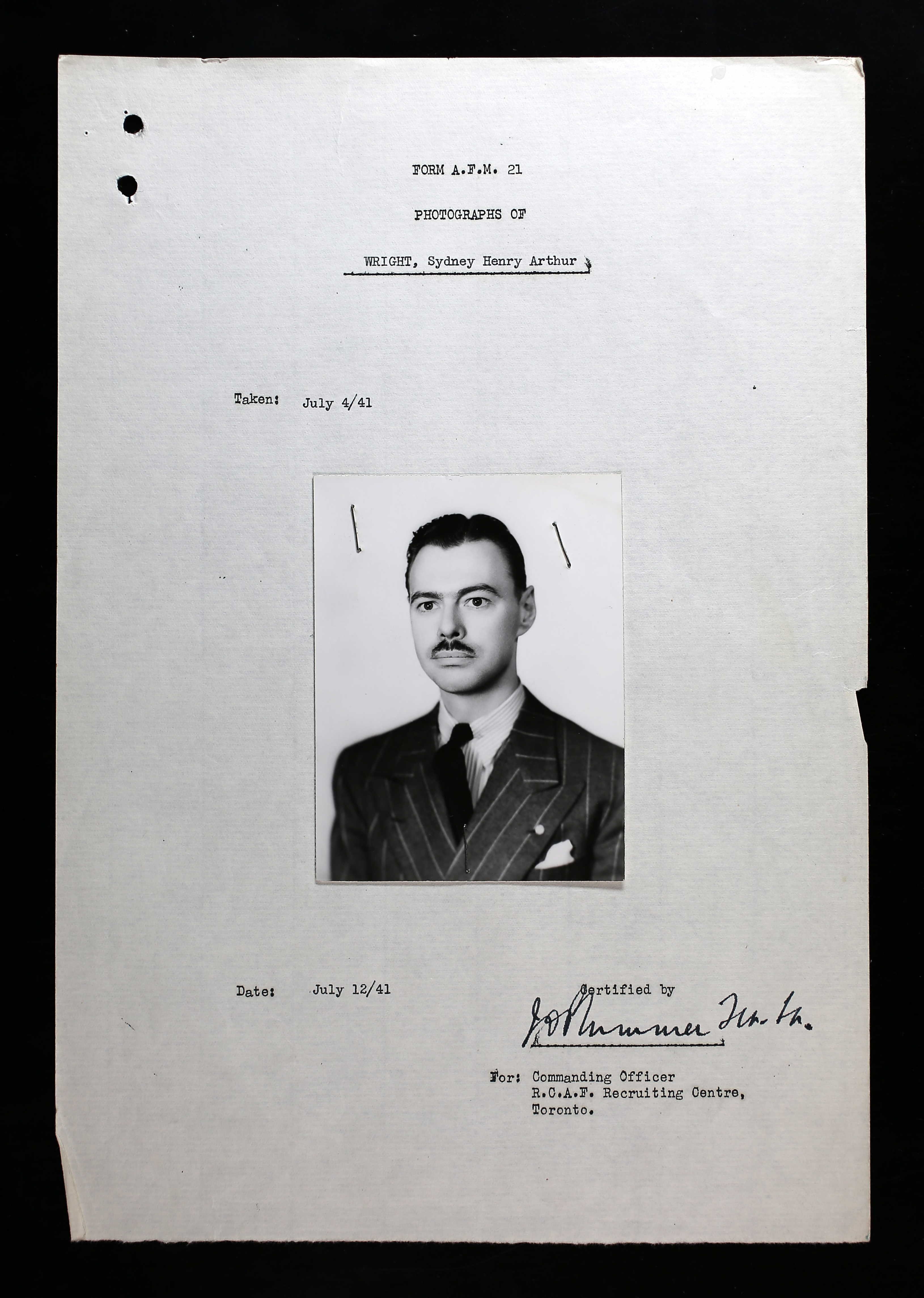

In July 1941, on his interview sheet, Sydney was noted as being confident, easy-going, neat, conservative, clean, slender, quick responsiveness, alert, and sincere, rated above average. “Keen intelligent, good appearance. Responsible, pleasant. Should be well suited for Regional Control Officer, alternatively as Administration or Accounts Officer.”

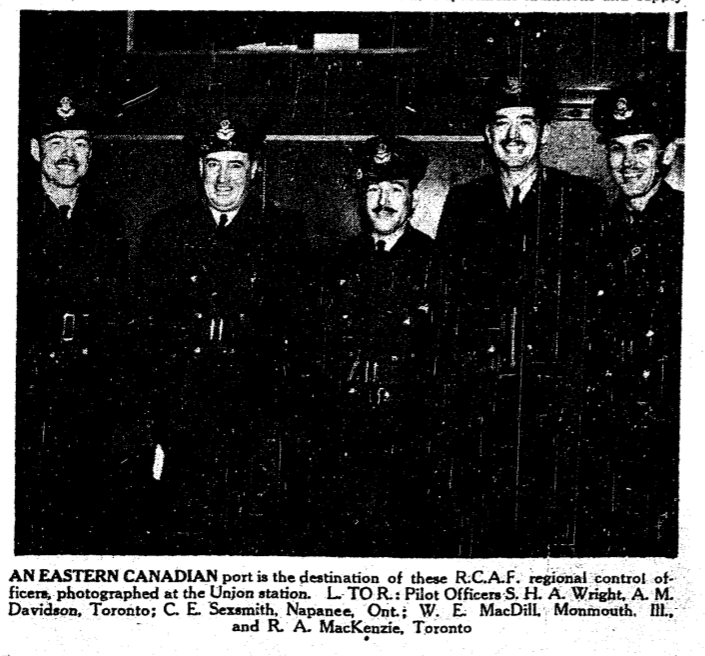

Sydney stood 5’ 10 ½” tall, weighing 140 pounds. He had brown eyes and brown hair with a medium complexion. On October 31, 1941, he was at Manning Depot until sent to No. 2 ANS, Pennfield Ridge, New Brunswick, November 13, 1941. He was then posted on December 17, 1941 to Y Depot, Halifax to head overseas.

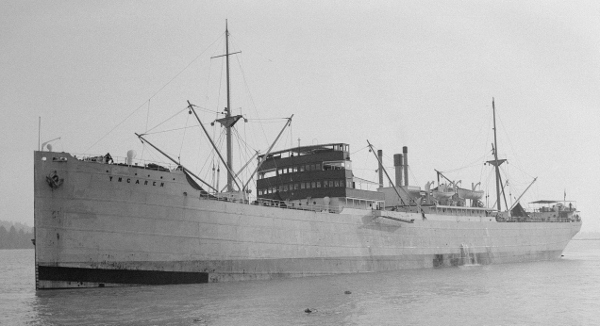

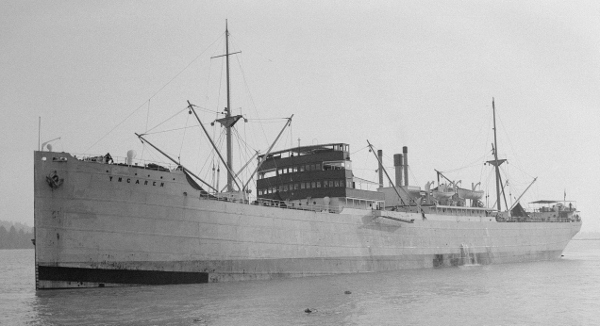

On January 12, 1942, Sydney was aboard the SS Hyngaren/Yngaren en route from Nova Scotia to the United Kingdom when it was torpedoed, sinking at 0400 hours. From u-boat.net: "At 08.02 hours on 12 Jan 1942 the unescorted Yngaren, a straggler from convoy HX-168 due to bad weather, was hit by two torpedoes from U-43 in heavy seas and sank within one minute about 600 miles west of Ireland."

On February 20, 1942, a letter was released with information. “Madame, I am commanded by the air council to express to you their great regret on learning from the Casualties Officer of the Royal Canadian Air Force that your husband, Pilot Officer Sidney Henry Arthur right, is missing and believed to have drowned at sea. Your husband was on board a vessel which set out from Nova Scotia for the United Kingdom, early in January. It is now long overdue and is presumed lost. Unhappily there is no news of any survivors. Enquiries are being made through the international Red Cross Society and if any information is received it will be at once conveyed to you. Should know definite news become available, the Council regrets that, in due course, it will be necessary for official purposes to presume your husband's death, and a further letter will then be addressed to you. The Air Council desires me to convey their great regret on receiving this news which, in the circumstances, unfortunately leaves so little room for hope, and to express their deep sympathy with you in your grave anxiety.”

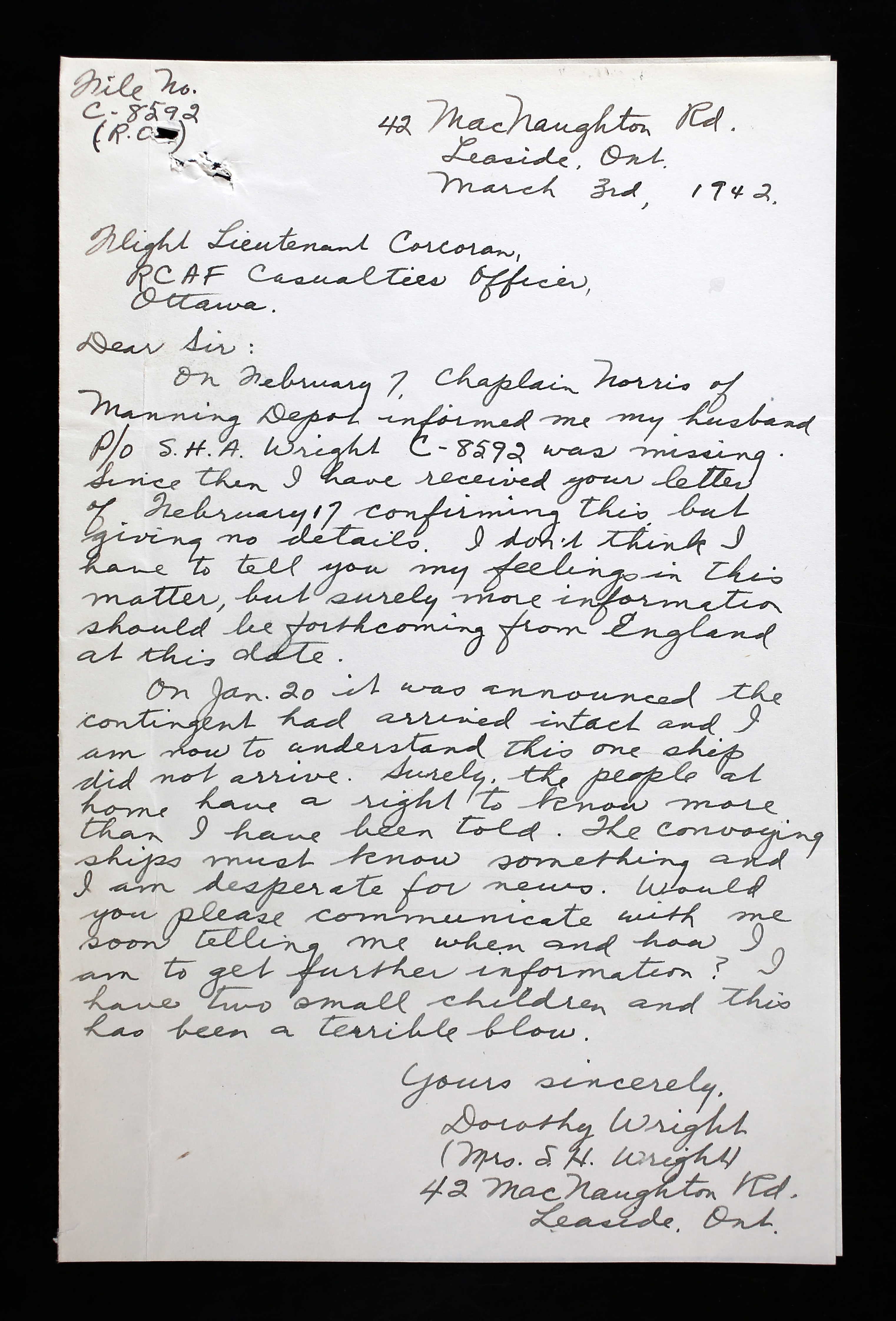

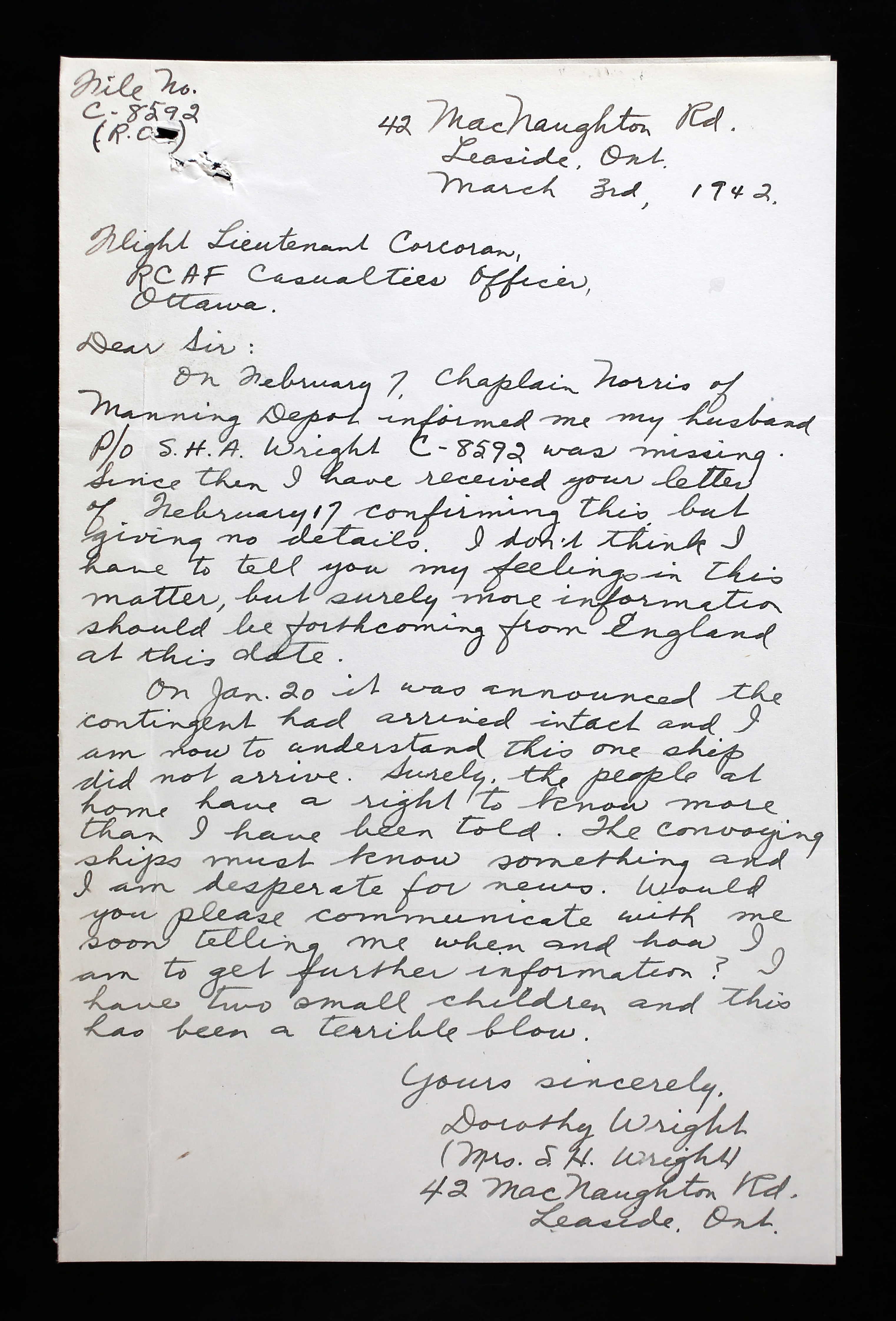

In a letter dated March 3, 1942, Dorothy wrote a letter. “On February 7, Chaplain Norris of Manning Depot informed me my husband…was missing. Since then I have received your letter of February 17, confirming this, but giving no details. I don’t think I have to tell you my feelings in this matter, but surely, more information should be forthcoming from England at this date. On January 20, it was announced the contingent had arrived intact and I am now to understand this one ship did not arrive. Surely, the people at home have a right to know more than I have been told. The convoying ships must know something and I am desperate for news. Would you please communicate with me soon telling me when and how I am to get further information? I have two small children and this has been a terrible blow.”

By June 15, 1942, Dorothy received another letter that all efforts to trace her husband’s whereabouts had proved unavailing.

On August 17, 1942, Dorothy wrote another letter. “During all these months I have hoped your office could tell me something. I still find it hard to believe that a con void ship disappeared so completely no one can say how or by what means. Yet I can't believe anything else since if any of the details were known after all these months surely, I could be told. It doesn't help any to read editorials in the papers to the effect that we have never lost a man on his way overseas.”

In a letter dated September 29, 1942, Dorothy received a letter with more information. “It is now definitely established by the Admiralty that the ship on which your husband was on passage from Nova Scotia to the United Kingdom was torpedoed and sunk at 4:00 AM on January 12 1942, and that, inconsequence of the lapse of time in the absence of any further news of him, his death has now been officially presumed to have occurred on that date.”

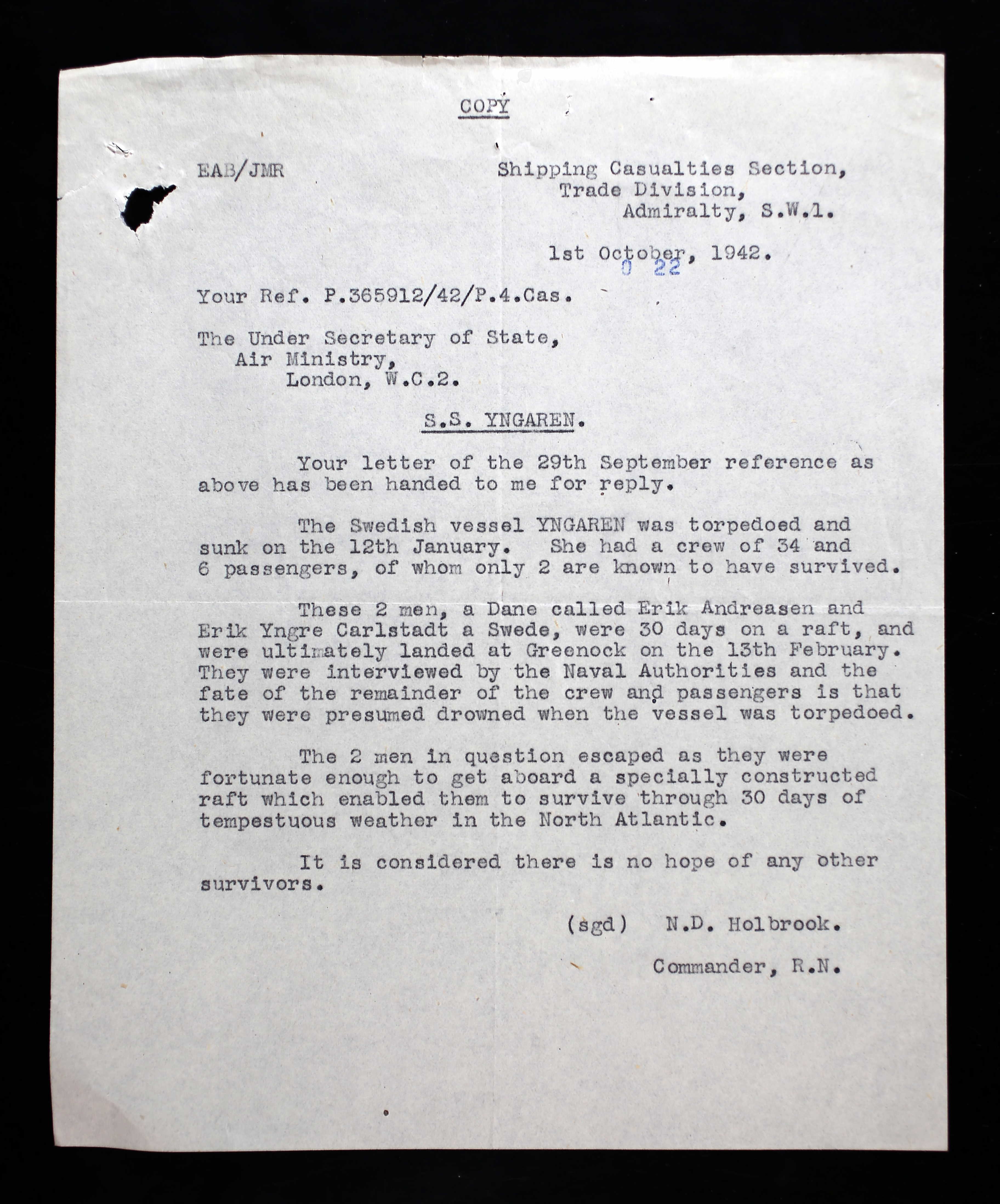

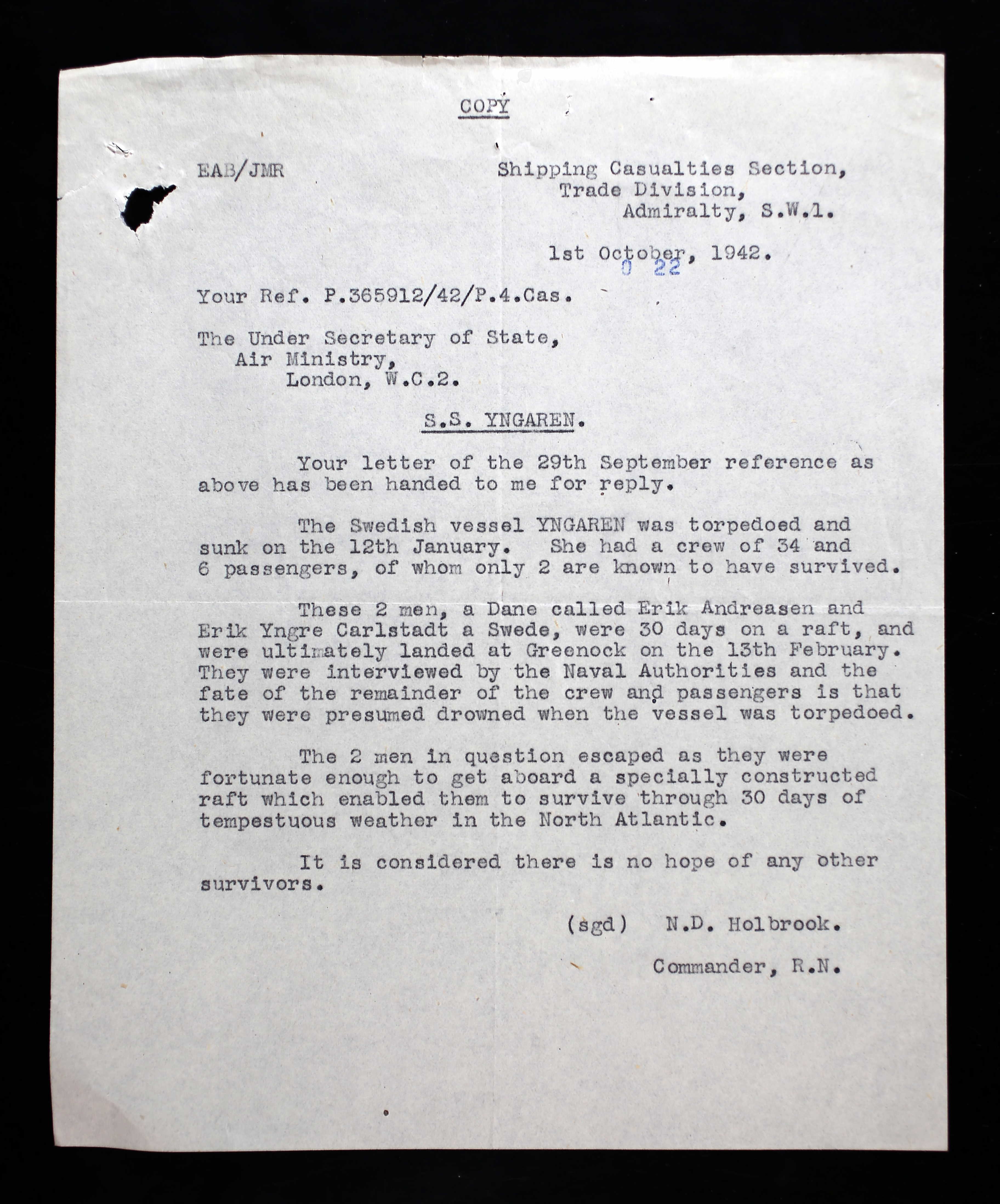

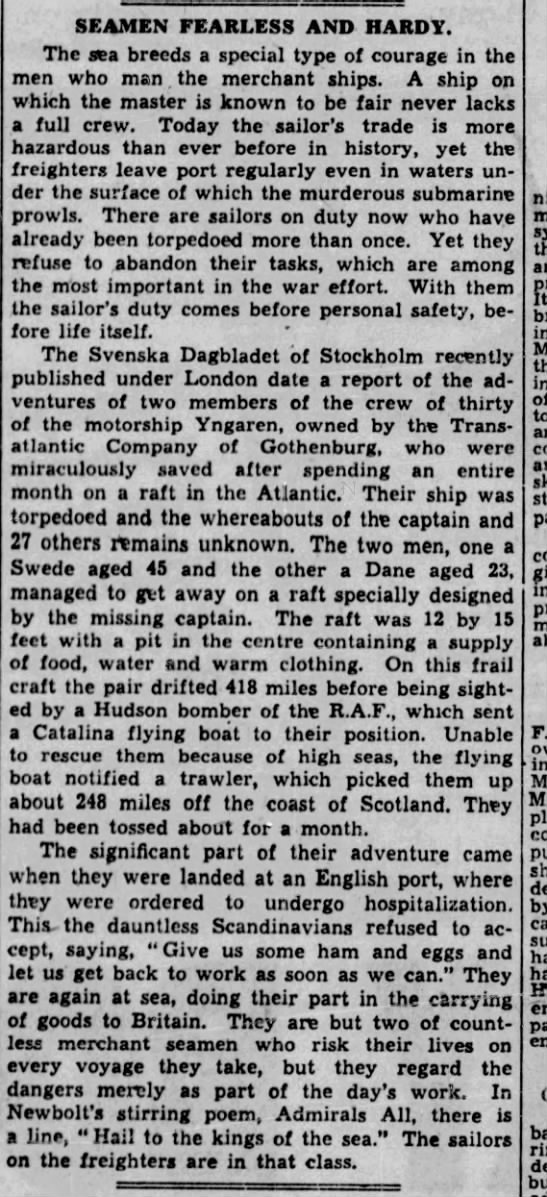

In a letter dated October 1, 1942 to the Under Secretary of State, Air Ministry, London, England from the Shipping Casualties Section, Trade Division, Admiralty: “The Swedish vessel Yngaren was torpedoed and sunk on the 12th of January. She had a crew of 34 and 6 passengers, of whom only 2 are known to have survived. These 2 men, a Dane called Erik Andreasen and Erik Yngre Carlstadt, a Swede, were 30 days on a raft and were ultimately landed at Greenock on the 13th February. They were interviewed by the Naval Authorities and the fate of the remainder of the crew and passengers is that they were presumed drowned when the vessel was torpedoed. The 2 men in question escaped as they were fortunate enough to get aboard a specially constructed raft which enabled them to survive through 30 days of tempestuous weather in the North Atlantic. It is considered there is no hope of any other survivors.”

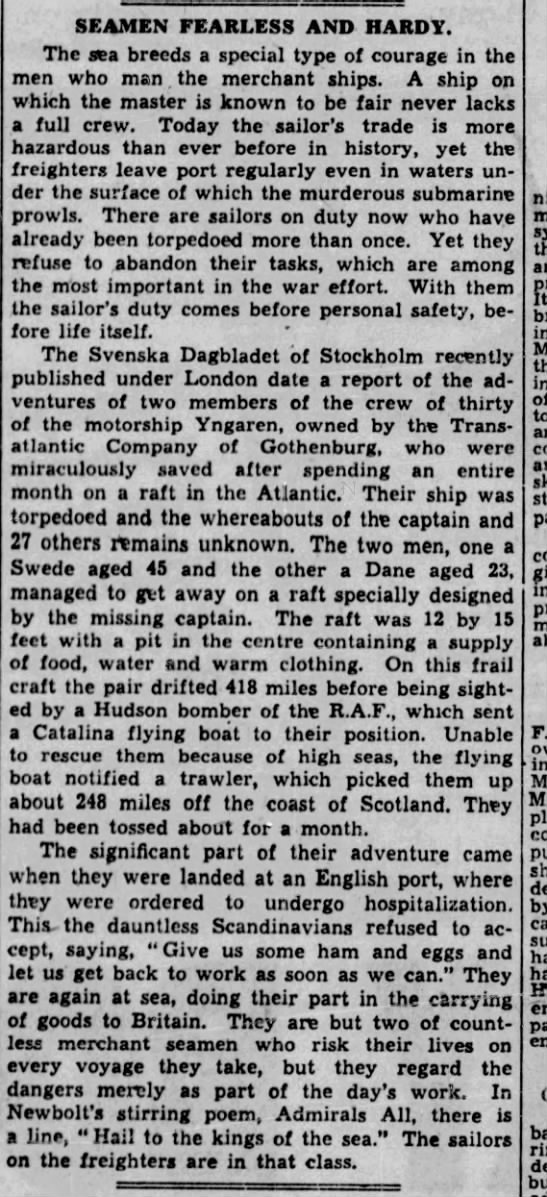

In an article from the Montreal Gazette, the men were 45 and 23 years old. The raft was 12 x 15 feet with a pit in the centre containing a supply of food, water, and warm clothing. “On this frail craft, the pair drifted 418 miles before being sighted by a Hudson bomber of the RAF which sent a Catalina flying boat to their position. Unable to rescue them because of high seas, the flying boat notified a trawler, which picked them up about 248 miles off the coast of Scotland. They. had been tossed about for a month. The significant part of their adventure came when they were landed at an English port where they were ordered to undergo hospitalization. This, the dauntless Scandinavians refused to accept except saying, ‘Give us some ham and eggs and let us get back to work as soon as we can.’ They are again at sea, doing their part in the carrying of goods to Britain.”

In late October 1955, Mrs. Wright received a letter informing her that since her son had no known grave, his name would appear on the Ottawa Memorial.

LINKS: