June 24, 1917 - August 23, 1942

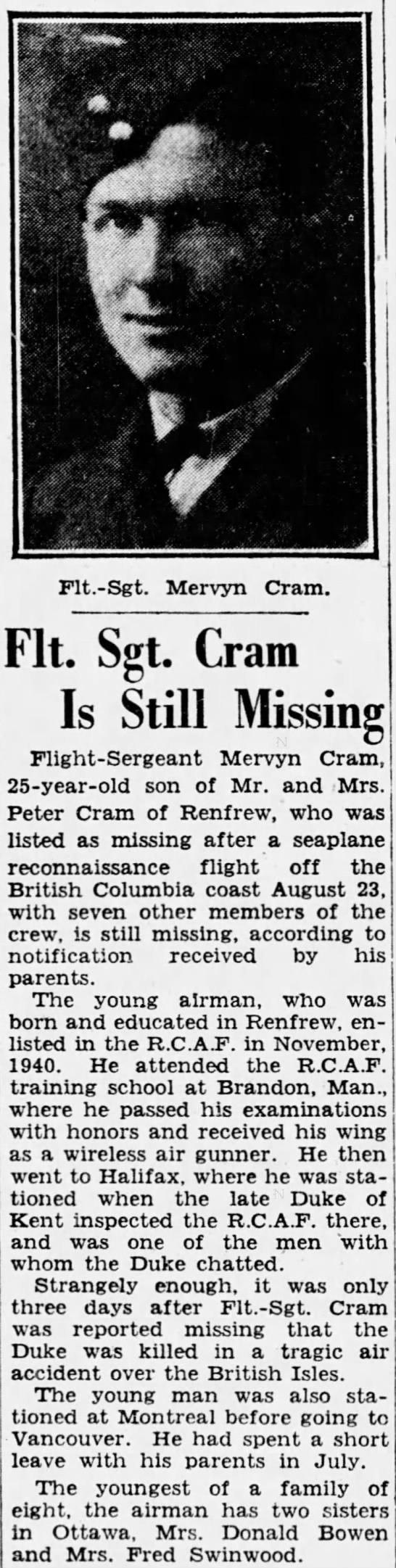

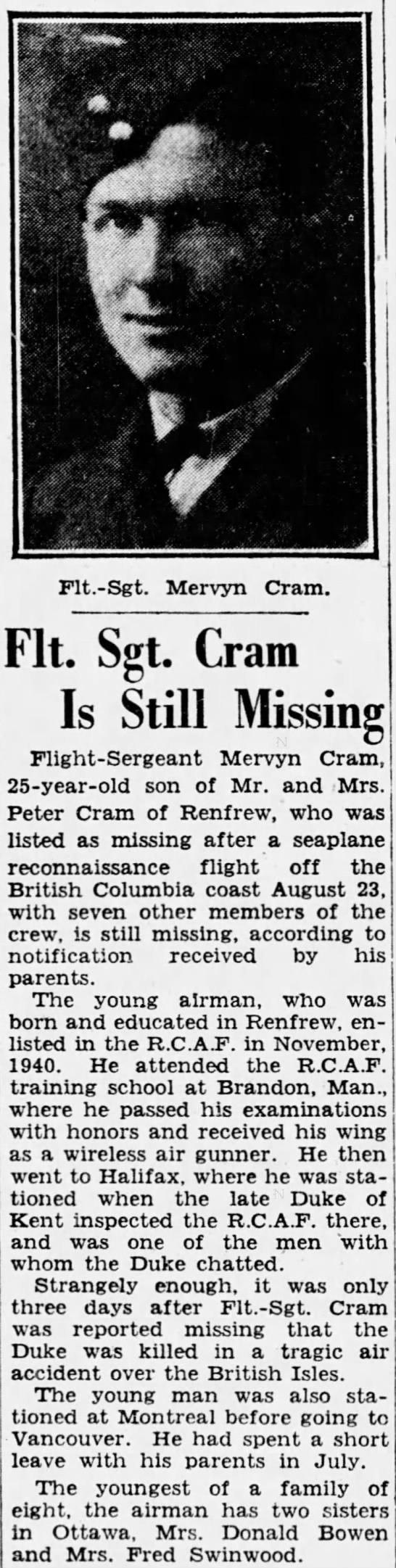

Mervyn Cram, born in Renfrew, Ontario, was the youngest child of Peter Cram (1867-1942), carpenter, and Harriet Mary (nee Bromley) Cram (1875-1958) of City View, Ontario (Ottawa). He had five sisters, Thurza Livingston (1902-1992), Margaret Emon (1895-1971), Iva Bowen (1905-1992), Ethel Bowen (1908-1970), and Agnes Bell Swinwood (1915-1999), plus two brothers, Harvey (1908-1994) and Lorne (1900-1983). An infant sister was stillborn. The family was Baptist.

Mervyn was a foreman a Renfrew Electric and Refrigerator Co. Ltd. for five years prior to enlistment with the RCAF in October 1940, wishing to be an equipment assistant. He had $9.13 in his joint bank account with his mother. He also had a life insurance policy, his mother beneficiary. He indicated he wanted to remain in the RCAF after the war.

Mervyn noted on his attestation forms that he got “kicks out of swings, roundabouts, and switchbacks.” He had been in the Boy Scouts as a child and worked on motors as a hobby, had three years of high school cadets, liked boxing, wrestling, baseball, hockey and was a collegiate champion in boxing. He smoked 3-4 cigarettes per day and had only one bottle of beer in four months. “Applicant is very enthusiastic and keen to serve in the air. He is a nice young man, polite, confident, quick and alert. Good material for Air Crew. Best fitted for W. O. Air Gunner.”

“A good candidate but is underweight. Should put on at least five pounds and then return for re-examination. Unfit.” Mervyn stood 5’6 ½” tall and weighed 112 pounds. Another note indicated the RCAF wanted him to put on eight pounds. By November 9, 1940, Mervyn had gained 10 pounds. His blue eyes, brown hair and medium complexion were noted.

Mervyn was first sent to No. 2 Manning Depot, Brandon, Manitoba November 21, 1940 until Jaunary 2, 1941, then was sent to Vancouver, BC until March 2, 1941.

Mervyn was at No, 2 Wireless School, Calgary, Alberta, from March 3 to July 20, 1941. He earned his Wireless Operator’s Badge on July 20, 1941, 13th in class out of 209, with a 79.6% average.

He was then sent to No. 7 B&G School, Paulson, Manitoba, until August 18, 1941. He was 25th out of 63 in his class in Gunnery. “Above average intelligence, alive, eager, energetic, quick thinking.” In Air Training, his final assessment was 8th out of 63. 77.4%.

Mervyn was sent to Halifax in August 1941, but then sent to Montreal, then to No. 31 O.T.U. Debert, Nova Scotia September 7, 1941 until December 13, 1941. In October 1941, he was at the Royal Victoria Hospital, Montreal. Then he was sent across the country to Western Air Command in Victoria, then to No. 120 BR, Coal Harbour as of December 20, 1941.

In March 1942, he was evaluated above average on and off duty in dress, personal appearance and deportment. “Keen, smart, good type of NCO.”

From Aviation Safety Network: “At 1750 on August 23, 1942, Supermarine Stranraer 951 of 120 (BR) Squadron RCAF, with a crew of eight was on a routine combat patrol out of Coal Harbour, Vancouver Naval Air Station Base when it suffered engine failure and was forced to ditch. An SOS was received at 18.18 hours to say that it was sinking. A search located the aircraft but due to high sea conditions, rescue was impossible. Later searches failed to locate the aircraft or crew and they were lost without further trace.”

Crew: • F/S Everard Thomas Cox (Captain) Vancouver, BC • F/S Lawrence Alfred Bernard Horn, (2nd Pilot) Regina, Sask. • Sgt Robert Bruce Stuart, (Observer) Vancouver, BC • F/S Mervyn Cram, (WAG) Renfrew, Ont. • Sgt Adolph Willard Anderson, (WAG) Selkirk, Man (under training) • Sgt Kenneth Earl Hope, (AFM) Vancouver, BC • Sgt Leslie Oldford, (AEM) Penhold, Alta • Sgt Charles Franklin Beeching, (AEM) Regina, Sask.

From the Court of Inquiry: “One man in excess of the normal crew of seven was carried. This airman was a WAG under instruction…the aircraft was not overloaded…equipped with one dinghy which would accommodate five men. One spare dinghy was available at the Station which could have been drawn by the captain of the aircraft but was not. Two rescue boats…attempted to reach the aircraft…but due to high seas and failure of radio returned to base. One reached the reported position before daylight the morning following the crash but could not locate the aircraft. The captain of the sighting aircraft carried only one dingy and was having trouble with both engines during the time he circled above the aircraft hence he did not drop his dinghy.”

A letter dated August 28, 1942, Coal Harbour, addressed to Mervyn’s father, stated: “It is with deepest regret that I have to inform you, that although every means is being used to find your son, there is very little possibility of now doing so. The search which has been carried out ceaselessly since the disappearance of the aircraft is still continuing and will for some time, but the only possibility for the crew’s survival which seems to be left, is that an outbound freighter may have picked them up. This is barely possible and owing to strict enforcement of wireless silence, word could not be sent back. This possibility I am afraid is very slim. I can well understand the grief this has brought to you because I have seen the fine comradeship your son Flight Sergeant Mervyn Cram created about him among the men of my squadron. We who have associated with him and worked with him day by day share your grief and great sense of loss. As a wireless operator, your son was considered outstanding on this station and as a man he ranked among our best. If he has not survived, which now seems to be so certain, you can rest assured he died at his post, serving his country to the last because he was that type of man. The aircraft was lost on a routine patrol, and should any further information be obtained you shall be immediately notified.” S/L P. B. Cox

In late October 1955, Mrs. Cram received a letter informing her that since Mervyn had no known grave, his name would appear on the Ottawa Memorial. It is unknown if she and her surviving children attended the unveiling.

LINKS: