December 2, 1915 - April 22, 1943

Merle Johnson, born in Fraserton, 28 miles south of Hanna, Alberta was the son of Alexander Johnson (1889-1917), farmer and carpenter, and his wife, Mildred Ileen (nee McClellan) Johnson (1895-1975). He had two full brothers: Alexander, 30, and John, 26. Alexander was farming in the Hanna area. John was overseas.

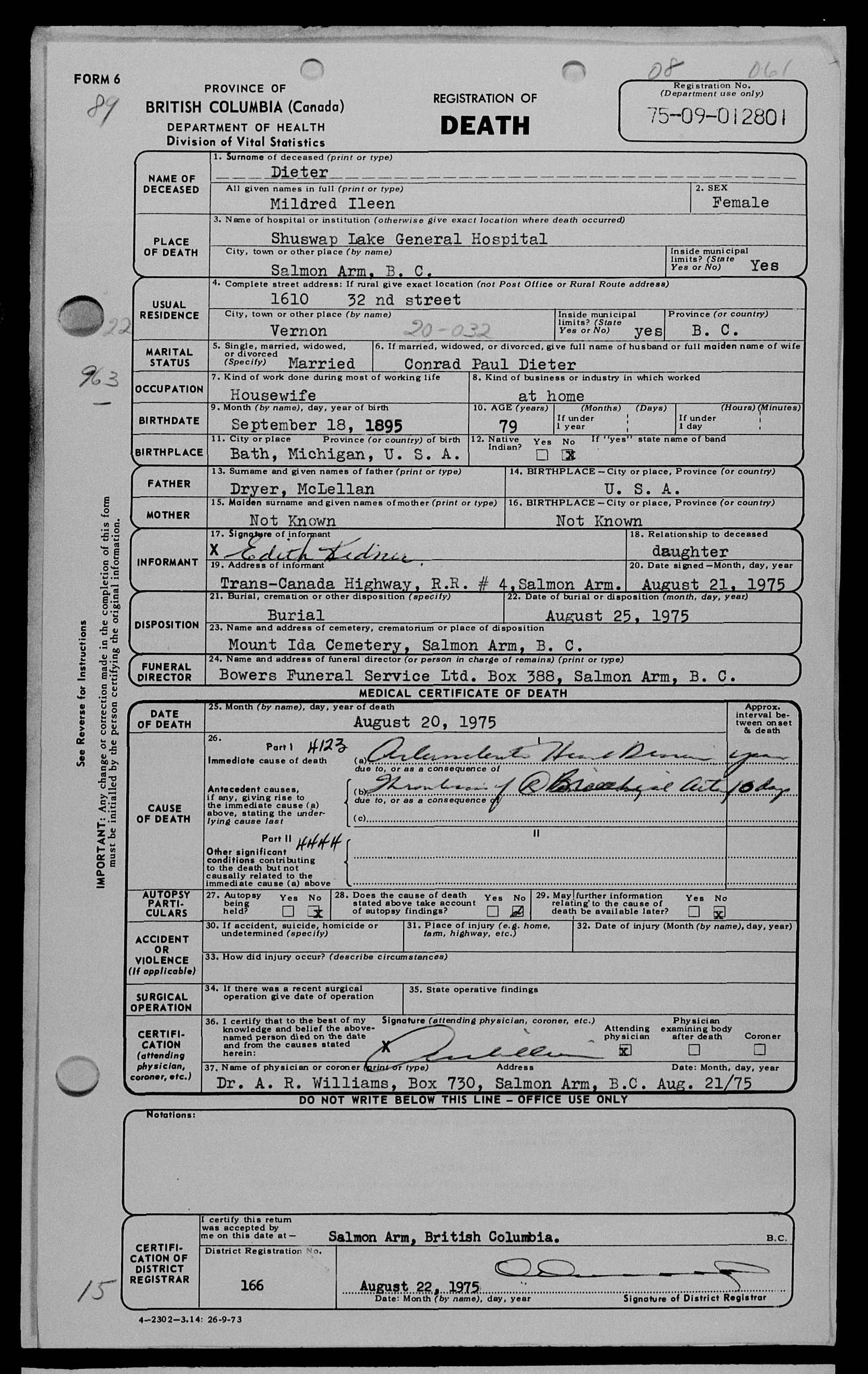

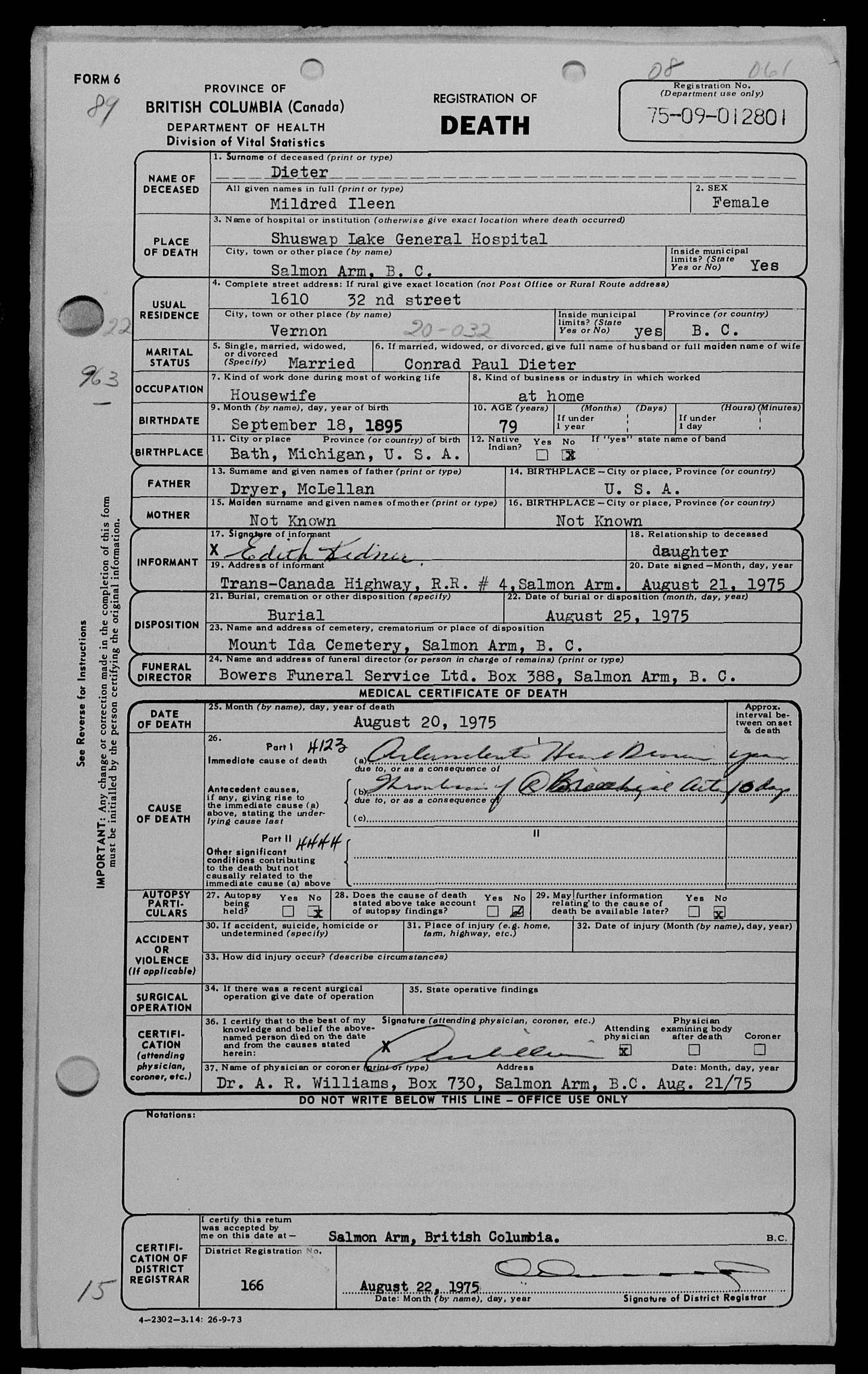

Merle’s father died of the flu at the age of 28, in 1917. Mrs. Johnson married P. J. or F. P. Murphy of Hanna, and with him she had five children: Peter, 9, Adrian, 8, Alice, 21, Betty, 18, and Edith, 16, as of 1944. The family moved to Salmon Arm, BC at some point. Mildred married Conrad Paul Dieter, who survived her.

After Grade XII, Merle worked at odd jobs, including construction, welding, and blacksmithing from 1933 to 1942. He said he would like to return to his former position in a machine shop after the war.

Merle, single, 27 years old, attested in Calgary, Alberta on May 11, 1942. He stood 5’ 8 ¼” tall, weighed 154 pounds, had a fair complexion, grey eyes and blonde hair. He had burn scars on lateral side right upper forearm, had broken his leg six months prior, but had healed well. He liked football and swam occasionally. He smoked 15 to 20 cigarettes a day, but indicated he did not consume alcohol. He had injured his left eye in 1941.

He had been a passenger in an airplane for 90 minutes and requested to be an Observer.

“Physique: athletic. Mentality: standard. Average pilot material. Average observer material. Intelligent, but long out of school. Fair motives and enthusiasm. Reactions quick. Slightly tense. Ocular muscle imbalance.”

He was sent to No. 3 Manning Depot, Edmonton, Alberta on May 30 until August 29, 1942. He moved over to No. 4 Initial Training School, remaining in Edmonton until November 21, 1942. “Highway building and airport construction, machinery supervisor and welder. Average sports, high strung, active, ordinary type, not outstanding. Alternative: Wireless Air Gunner.” He was 48th out of 105 students in Course 62 with a 78% average.

From there, he went to No. 2 Bomb and Gunnery School, Mossbank, Saskatchewan. Here he received a total 72.6%. He was 14th out of 24 in class.

At No. 3 Air Observer School in Pearce, Alberta he received a 67.4% and was there until April 3, 1943 where he earned his Air Observer’s Badge on March 19, 1943 and a commission. “Above average student. Bombing: A very good bomb aimer. The assessment and scores are not indicative of his work. High winds, poor visibility and cold proved a definite handicap. Gunnery: High average. Navigation: Above average. His air work is good. Armament: very good in armament. General: Neat appearance. Well mannered. Conscientious. Officer material.” He was 7th out of 33 students. “Academically above average. A steady hard worker who was highly respected for his ability and sincere work.”

By April 4, 1943, Merle was at Y Depot, Halifax, and awaiting transport overseas. Some time later, he, with 36 other RCAF airmen, boarded the Amerika. On April 22, while on its way from Halifax, Nova Scotia to Liverpool, it was torpedoed as the ship was heading to Britain. It was a straggler in convoy HX-234. Thirty-seven men, all officers in the RCAF, were presumed missing as a result of enemy action at sea including Merle. Their ship was sunk by U-306, south of Cape Farewell, off Greenland.

Forty-two crew members and seven gunners were also amongst those who were lost. The master, Christian Nielsen, 29 crewmembers, eight gunners, and sixteen passengers (RCAF airmen) were picked up by the HMS Asphodel, and landed at Greenock. General cargo, including metal, flour, meat and 200 bags of mail were also lost.

Mrs. Murphy received a letter in June 1943 from F/L W. R. Gunn, RCAF Casualties Officer for Chief of the Air Staff. "Since my letter of May 6th, no additional news has been received. Attached is a list of the names and next-of-kin of sixteen Royal Canadian Air Force officers who embarked on the same ship as your son and following enemy action at sea were safely landed in the United Kingdom. The following official statement was made in the House of Commons....’I have been in receipt of communications from a number of members of this house and from people outside with reference to rumours regarding the recent loss of a number of members of the RCAF by the sinking of a ship in the north Atlantic and I desire to make the following statement on the facts. The vessel in question was a ship of British registry of 8,862 tons, designed for peace-time carriage of both passengers and freight, and having a speed of fifteen knots. She carried a crew of 86 and the passenger accommodation consisted of 12 two-berth rooms with bath and 29 other berths, providing cabin accommodations for 53 passengers. She was fitted with lifeboat capacity for 231 and travelled in naval convoy. Under the recently revised regulations agreed to by the United States authorities, the joint United Kingdom and United States shipping board, the Admiralty, the Air Ministry and the Canadian authorities, a vessel of this description travelling in convoy is permitted to embark as crew and passengers a maximum of 75% of the lifeboat capacity. The lifeboat capacity as stated above was 231, 75% of which is 173. Personnel on board consisted of the crew of 86, and RCAF personnel numbering 53, a total of 139, well within the prescribed limits. Because of the superior type of available passenger accommodation, the speed of the ship and the provision of naval convoy, the offer of the entire available space to the RCAF was immediately accepted. Rumours to the effect that this was a slow freighter not suitable for passenger accommodation are, of course, not in accord with the facts. Every precaution was taken to safeguard the lives of these gallant young men. It should be pointed out that on account of the serious shipping shortage every available berth on such ships must be used, and had the space not been taken up by the RCAF officers of the other arms of the services would have been placed on Board. It should also be stated again that the submarine is still the enemy’s most powerful weapon and that the Battle of the Atlantic is not yet won. Any ocean trip today in any part of the world is fraught with danger and I think I may safely say that our record in transporting our soldiers and airmen to the United Kingdom is one of while we may all be proud. No one deplores more than I do the loss of 37 of the finest of our young men who gave their lives for their country as surely as if they had done so in actual combat with the enemy, and I extend my deepest sympathy to their loved ones in their bereavement.’ If further information becomes available, you are to be reassured it will be communicated to you at once. May I again extend to you my sincere sympathy in this time of great anxiety."

In early January 1944, Merle’s mother received another letter from S/L W. R. Gunn that Merle would now be presumed dead for official purposes.

By February 1946, Merle’s mother was living in Salmon Arm, BC. But his medals were returned undelivered in February 1950. “Returned to stock.”

It is unknown if in October 1955, she received the letter from W/C W. R. Gunn informing her that Merle’s name would appear on the Ottawa Memorial, as Merle had no known grave, expressing sympathy on the loss of her gallant son.