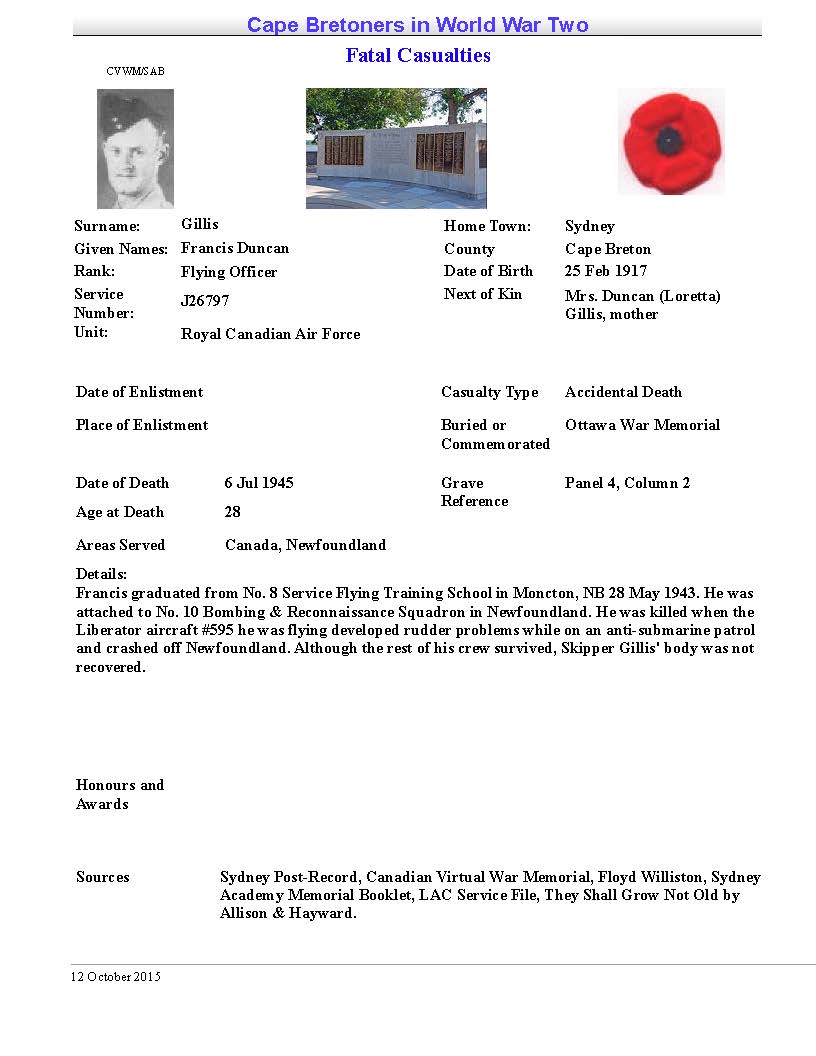

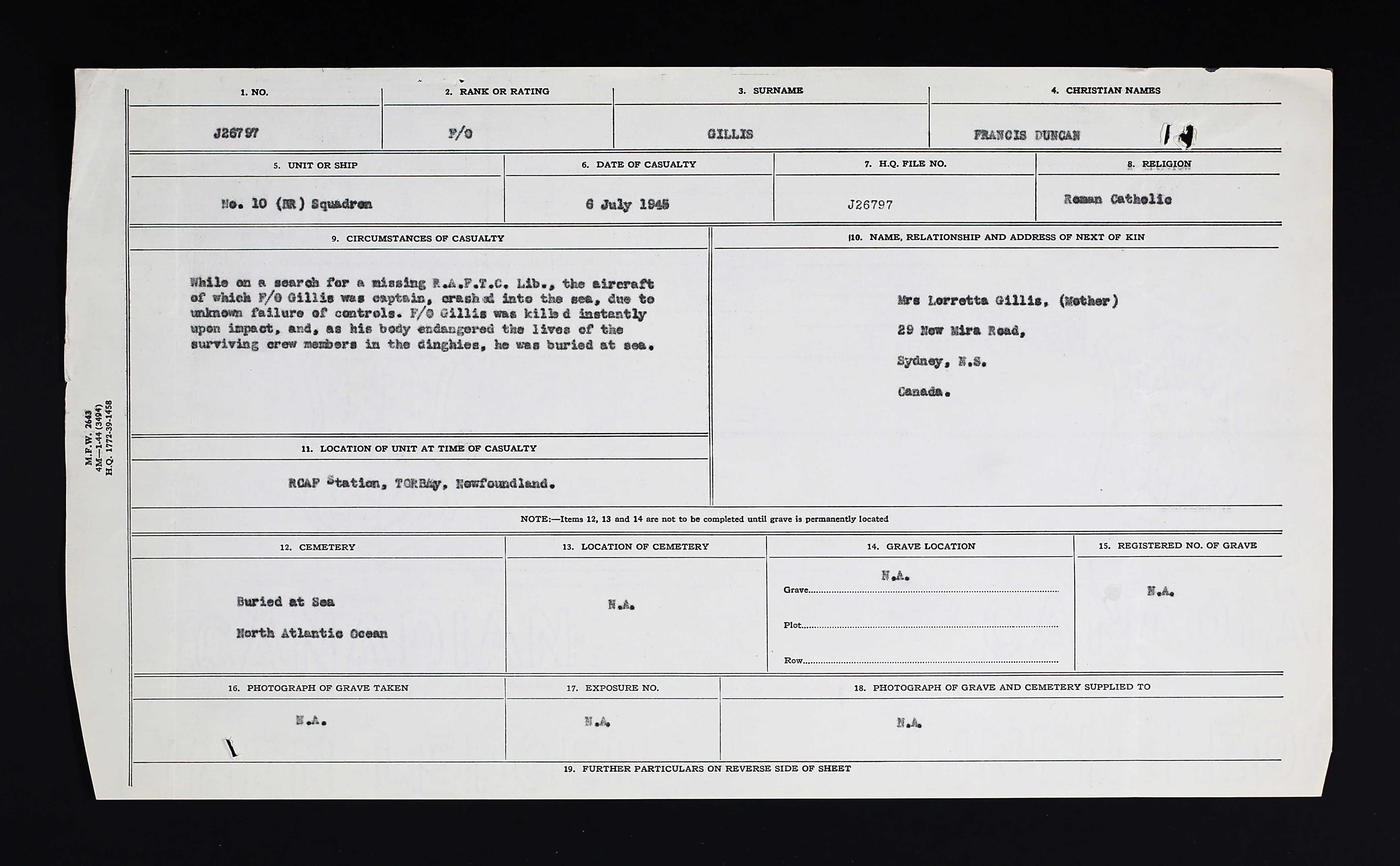

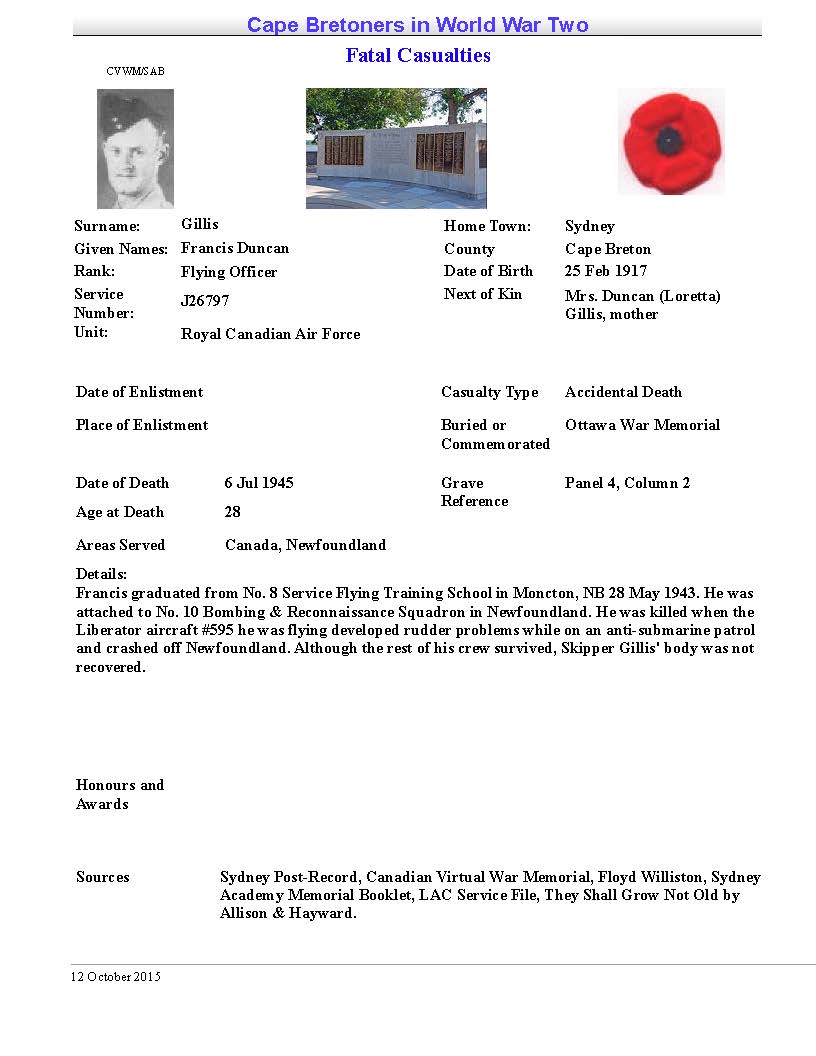

February 25, 1917 - July 6, 1945

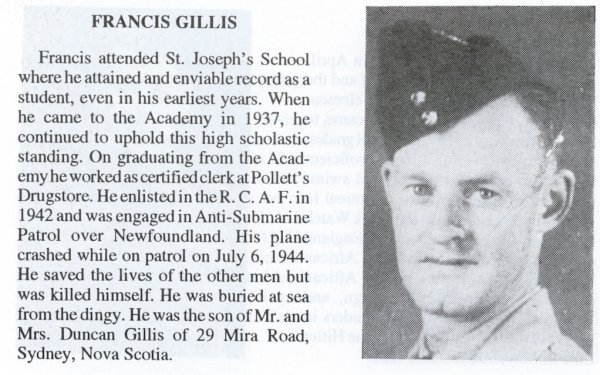

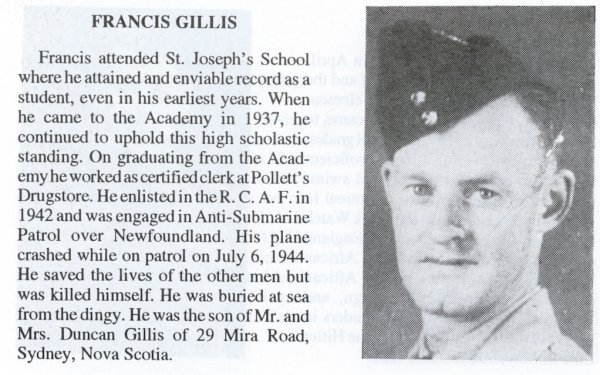

Francis Duncan Gillis was the son of Duncan Angus Gillis, salesman, and Loretta (nee Coady) Duncan of Sydney, Nova Scotia. He had two brothers, Hugh Joseph Gillis, with the Canadian Army, and Wilfred Donald Gillis, with the RCVNR, serving overseas. He also had one sister, Edith Theresa Gillis, at home. An infant sister died at birth. The family was Roman Catholic.

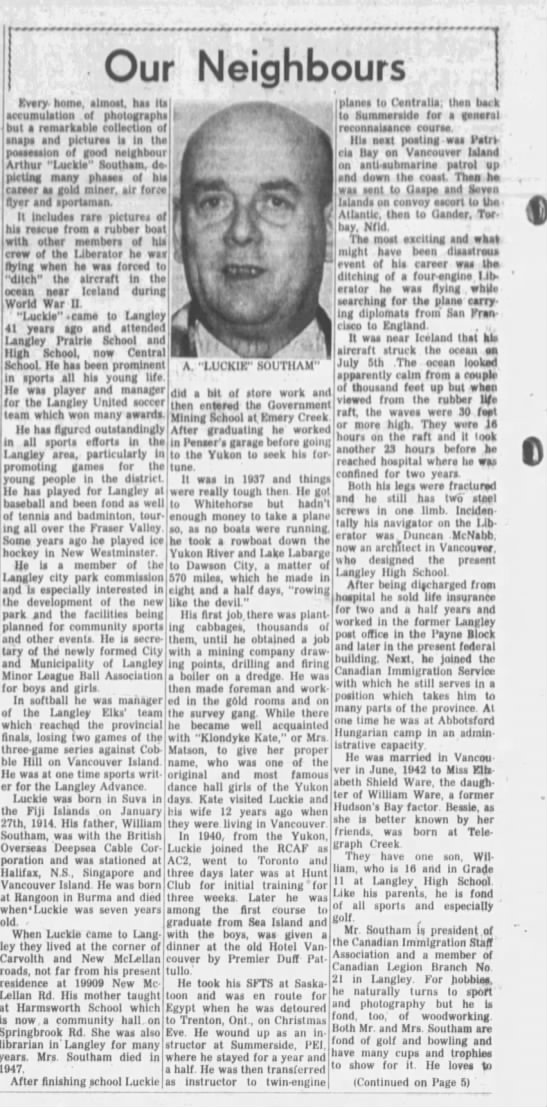

Francis was a drug clerk prior to his enlistment. He studied, by correspondence, elementary electricity and radio. He liked to skate, swim, and play tennis occasionally. He stood 5’8” tall and weighed 141 pounds. He had blue eyes and brown hair. Several of his lower molars were missing and he had an upper plate.

He purchased 2x$500 War Savings Certificates, 1x$50 bond and $1000 in Victory Loan bonds. He also had a life insurance policy.

May 6, 1942 at No. 16 Recruiting Centre, Halifax, Nova Scotia: “Deliberate, quick, understanding, taciturn, stable. Ability to learn. Personal background education: Completed Grade XII in 1935. Perfect marks in XI math. Very good in XII. “C” score shows excellent ability to learn. Certified drug clerk. Has been working at this for four years. Knows first aid well. Should be a good Observer.”

Francis started his journey through the BCATP at No. 5 Manning Depot, Lachine, Quebec on July 2, 1942, then was at No. 4 Manning Depot, Quebec the next day until September 12, 1942.

From September 14 to November 6, 1942, he was ITS, Victoriaville, QC and passed with 92%. He was 23rd out of 130 in his class. “Quiet. Reliable, serious and mature. Good aircrew material.”

He was then at EFTS, Windsor Mills, QC from December 7, 1942 to February 15, 1943, second in his class of fifteen, with 87.1%. “Careless about air speeds. Aerobatics are poor. Instrument flying is poor. Needs much practice in instruments. GIS: Excellent student. Co-operative and pleasant to work with.”

At SFTS, Moncton, NB from February 8 to May 28, 1943, he was 19th in his class out of 48 with 78.5%. Here, Francis earned his Pilot’s Flying Badge. “Above average pilot. Definite commission material. Link: 80.”

At No. 1 GRS, Summerside, PEI, June 7 - August 6, 1943: “78.9%. 5th out of 23 in class. A brilliant student and capable navigator. He has worked conscientiously throughout the course. Recommendation for future employment: GR Land Planes, Fighter Recco, Torpedo Bombers. An exceptional pupil. Very hard working and capable.”

November 11, 1943: “This officer has carried out his duties as an instructor for the past three months, in such a manner as shows him to be a satisfactory officer.” No. 1 GRS.

On May 14, 1944, he was taken on strength with No. 10 Squadron, Gander, Newfoundland. May 17, 1944: “This officer was a keen a conscientious instructor. He performed all his duties to the very best of his ability.” No. 1 GRS.

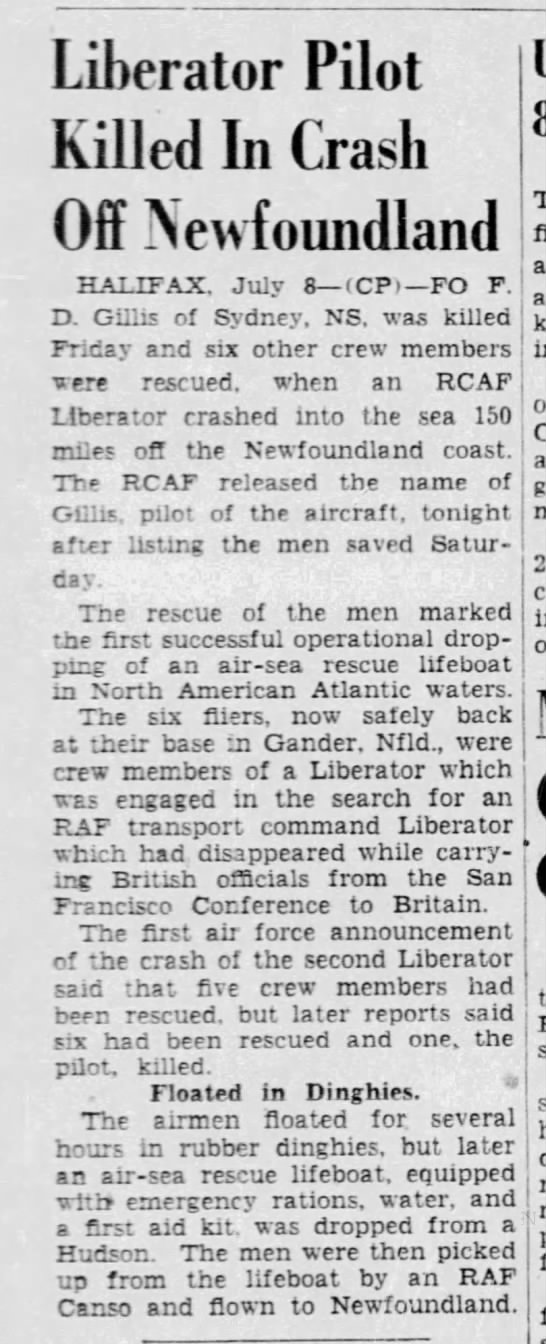

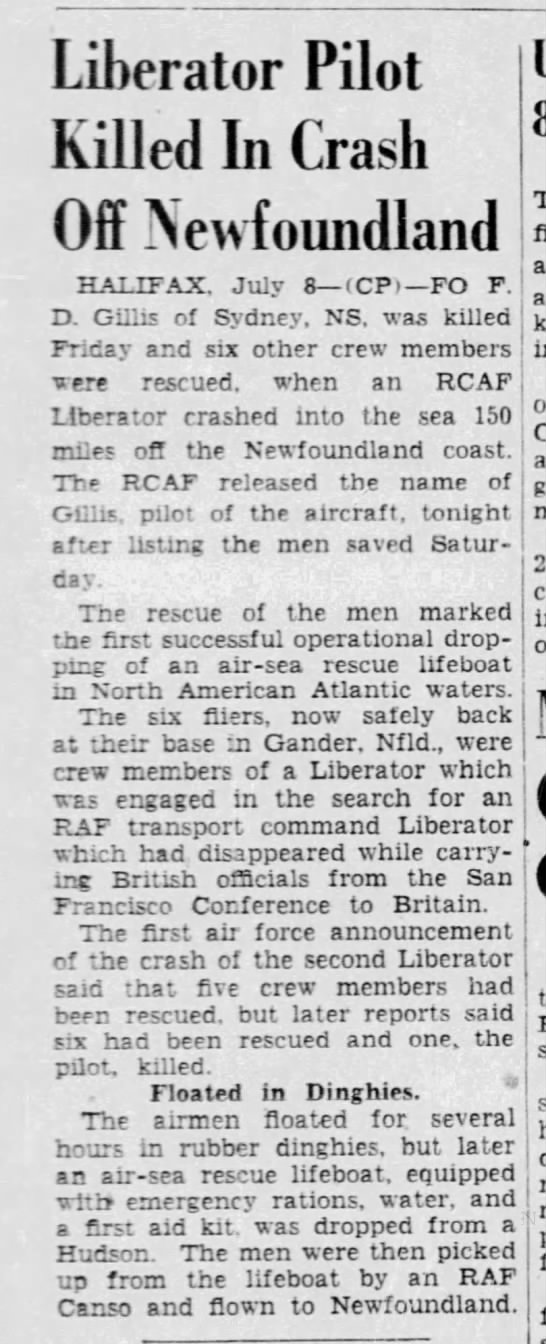

From Aviation Safety Net: “On July 6, 1945, RCAF 10 (BR) Squadron was involved in the continuing search for a missing RAF Ferry Command C.IX Liberator JT982, which had been on a route leg from RCAF Station Gander to Keflavik, Iceland. The aircraft carried 15 crew and passengers. Apparently, the Liberator had ditched into the North Atlantic on July 4, 1945 due to the elevator becoming jammed. Liberator GR.V/Can 595 X, of 10 (BR) Sqn, took off from RCAF Station Torbay to participate in the search mission. During the search, the RCAF Liberator itself ran into control difficulties and was forced to ditch in the Atlantic Ocean off Newfoundland. The pilot carried out a successful ditching which was practically impossible in a Liberator. Six of the seven crew were able to get out of the aircraft and into a dinghy, but unfortunately the pilot who was so successful in ditching the aircraft, perished. An RCAF Hudson of No. 1 (Composite) Squadron, located the missing crew of Liberator 595 X and dropped an air-sea rescue lifeboat. This marked the first successful operational dropping of an air-sea rescue lifeboat in Atlantic waters off North America. Subsequently, the six surviving crew members were picked up by an RAF Canso. Regrettably, no survivors were ever found from the missing Ferry Command Liberator.”

Aboard Liberator JT982: CREW: Capt. G. P. Evans, Pilot, US, Capt. J. W. Ross, Second Pilot, US, C. P. J. ‘Red’ Meagher, radio operator, Canadian, F/O Roy Holden Marshall Patterson, Navigator, RCAF, G. R. Swaney, Flight Engineer, US, Acting Sgt. W. T. Keats, Flight Clerk, RAF.

Passengers: Sir William Malkin, Colonel Denis Cuthbert Capel-Dunn, Mr. R. T. Peel, Miss M. J. C. Scupham, Miss J. M. Cole-Hamilton, Miss D. Smith, Miss R. Hibbert, Miss P. M. S. Spurway, and Miss A. M. Collard.

Liberator 595: “Killed July 6, 1945. Body recovered and committed to sea (aircraft flying at 800 feet). Crew heard a loud report and aircraft turned to port. It was impossible to control aircraft; the rudders jammed and it was impossible to hold aircraft with full starboard aileron.”

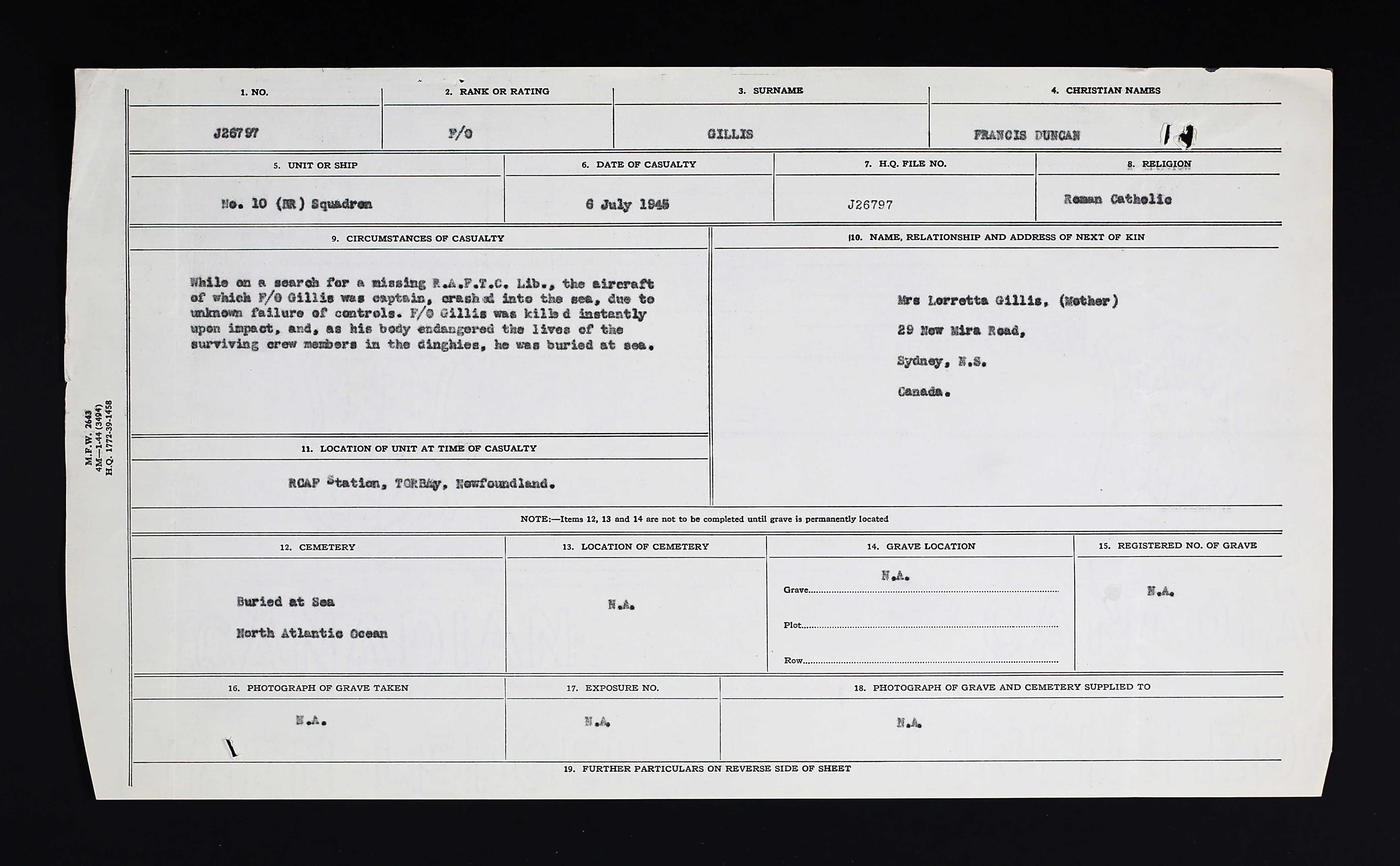

“While on a search for a missing RAFTC Liberator, the aircraft of which F/O Gillis was captain, crashed into the sea, due to unknown failure of controls. F/O Gillis was killed instantly upon impact and as his body endangered the lives of the surviving crew members in the dinghies, he was buried at sea.” [North Atlantic Ocean]

Due to the surmised structural failure, many memos and letters were noted discussing Liberator 595.

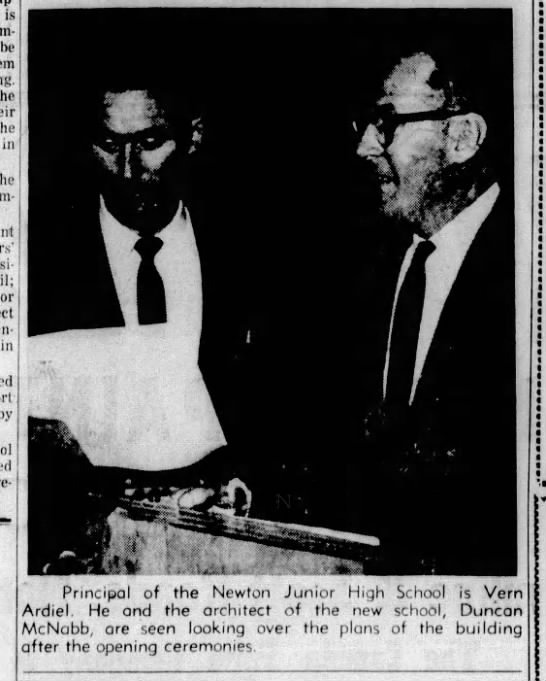

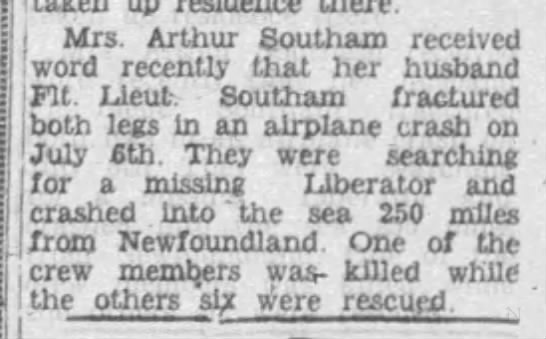

MEMO: July 7, 1945: “One RCAF officer was killed and six officers and airmen were rescued when the crew of an RCAF Liberator was forced down at sea at 8 am Friday 6 July during a search for the missing United Kingdom bound Liberator carrying British representatives from the San Francisco Conference to Great Britain it is announced by the Eastern Air Command HQ of the RCAF. After four hours afloat in dinghies and an airborne lifeboat, the men were picked up by a Canso aircraft and flown to hospital in Gander, Newfoundland. The Canso spent eighteen minutes on the sea affecting rescue. Names of the RCAF survivor members of 10 BR Squadron Torbay are F/L Arthur Fitzroy Southam, Second Pilot. His wife resides at Huron Street, Exeter, Ontario. F/L Duncan Stewart McNabb, Navigator, Boundary Bay, BC. F/S Burton Leroy Armstrong, WAG, Kingston, Nova Scotia. F/S James Astle Bates, WAG, Abbotsford, BC. F/O James Gordon McArthur, First WAG, Windsor, Ontario. P/O Robert Bayne Lundy, Flight Engineer, J48275, whose home address is not yet known. Name of the pilot who was killed is being withheld pending confirmation of notification of his death to his next of kin. Forced down when the aircraft when out of control about 8 am Friday. The survivors entered two rubber dinghies and shortly afterwards, four Liberator aircraft also engaged in the search for the missing UK bound craft were circling the position. A Hudson aircraft from RCAF Stn Torbay dropped an airborne lifeboat to the six airmen who entered the boat and were taken aboard the rescuing Canso around 1:00 o’clock in the afternoon. Injuries to the crew included minor lacerations and the effect of shock. All were under medical care in the Gander Station Hospital by 5:00 o’clock Friday afternoon. Not for release to press.”

The third witness, F/L D. S. McNabb, C9724, Navigator, said it was “just a matter or seconds from the time” he reached “the flight deck till we crashed.” He had felt something hit the back of the aircraft, sounding like a pistol shot. "We had insufficient height to carry out standard ditching procedure.” He was unable to open the front top hatch. “I observed the captain turn over the control of the aircraft to the co-pilot, F/L Southam, and commence to strap himself in as required by the ditching procedure…As we hit, the compartment filled with water and since I was not braced, the water cushioned me. The compartment filled instantaneously and I was under water. I could not get out the top hatch, so turned and swam down. F/S Armstrong followed me. I found an opening through which we swam up to the surface…one caused by impact. We came up to the surface forward of the mainplane in about the position where the nose of the aircraft should have been. I saw two dinghies, both upside down about ten feet away in front of the starboard wing. I noticed that the nose of the aircraft was gone. The bomb-bay tank was about ten feet in front of the starboard wing about 20 feet from me. The starboard wing was floating engines down. It seemed to be attached to the wreckage of the fuselage. I saw no sign of the port wing or engines. Small bits of wreckage were scattered over an area of about 100 feet. Wreckage of the fuselage was under water about three feet. F/S Armstrong came to the surface beside me, F/O McArthur was on the starboard wing sitting up on the trailing edge. I saw F/L Southam in the water some distance in front of the starboard wing. He seemed to be supporting himself on something. At the moment I do not remember seeing any others. All I saw seemed to be alright. I righted one of the dinghies and helped Armstrong in it. Southam was hanging onto it. He told me his two legs were broken. I now saw F/O Gillis, the captain, near the tail of the aircraft about 15 yards away. The tail was under 2 feet of water. I have not yet seen two other members of the crew, Lundy and Bates, so far as I now remember. All crew members when I observed were conscious and taken care of for the time being except the captain. I called to him several times but he did not answer. I got off the dinghy and swam to him. He sank as I approached him but I was able to get him. That is when I saw the wreckage of the tail section as I took it to be. It was about three feet underwater and completely twisted out of shape. It is possible it could have been the port wing which had struck first. In any event, it was at right angles to the starboard wing which was still afloat. This may have given me the impression that it was the tail section. I swam back to the dinghy with Gillis and had difficulty keeping his head out of the water. He was unconscious. As I reached the dinghy, McArthur who had now reached it helped me get Gillis in. This was the 2nd dinghy. It had not been righted so actually we were on top of it in the inverted position. By this time Lundy and Bates had reached the first mentioned dinghy. The lads at this dinghy got themselves out of the water. The two dinghies were side by side. Southam was sitting on the edge of the first mentioned dinghy with his legs hanging over the side. I saw that both legs were broken. They seemed to be shapeless and both were bleeding. I went over to the first dinghy and pulled Lundy in it. I then returned to the other dinghy and examined Gillis. When I first got to him, my impression was that he was quite unconscious. His eyes were wide open and his body limp. When I reached him, he did not move or offer any resistance contrary to my expectation. When I got him on the second dinghy, I noticed that his face was purple and that there was foam about his nose and mouth. I tested his lungs and heart but could not detect any movement or sign of life. The foam covering his nose and mouth gave an indication of breathing. His eyes were open but not focused. McArthur also examined Gillis and decided that he was dead. I was of the same opinion. As we crashed we had not sent out our position. There were a lot of ropes around stitched to the dinghies, some of which we thought were also stitched to the aircraft which was beginning to sink and it appeared that the aircraft might pull the dinghies down with it. Actually, only one of these ropes was attached the aircraft; this rope was partially around Armstrong's leg but was not attached to either dinghy. Fortunately Armstrong was able to free himself. In this situation with an expectation of having to spend a long time in the dinghy and being satisfied that Gillis was dead, MacArthur and I decided to let his body overboard, which we did. The other crew members were suffering from shock or preoccupied with their own injuries and did not participate in this decision. We then righted the second dinghy and distributed the crew members three to a dinghy. We obtained one sleeping bag from the floating wreckage and used the lining to cover them. In the course of about half an hour, we were sighted by one of the Liberator aircraft and a few minutes later by another. The water was very cold and we were all suffering from and shaking from exposure and shock. It cheered us greatly to see these aircraft, one of which dropped Lindholme gear. It was dropped about 200 yards away. We expected to drift to it and did not consider it wise to expend our energy paddling to it. We did not see it again. Later, a Hudson aircraft flew over and dropped an air sea rescue boat. It was a perfect drop about 40 yards downwind from us. We paddled to it and got on it. We were apprehensive about moving from the dinghy. Before making any decision, Canso FT 998 (Canso ‘A’) arrived and picked up all of us and took us to Gander. We were in the water 6 hours. I omitted to state above that after righting the dinghies we tied them together.”

McNabb suffered lacerations about his face and scattered abrasions and contusions. Southam stated that the post wing and tail struck the water at the same time at about 140-150 mph, still under full power 200 miles NE of Torbay.” He suffered a bilateral compound fracture of tibia and fibula. Bates suffered from multiple lacerations and abrasions, plus first-degree gasoline burns to his neck, back, and buttocks. Armstrong’s injuries were sustained during crash or while swimming under water trying to find his way out of the aircraft, including laceration of his scalp and left knee, plus contused chest.” McArthur “heard a sharp explosion, like a static discharge belt or cable snapping, and warned that something was radically wrong. He had time to don his Mae West and hand other WAG also in rear his Mae West. "Aircraft pulled sharply to port and losing altitude rapidly, sudden dip to port and then crashed.” He suffered from a puncture wound dorsum of his right hand, and gasoline burns left thigh and buttocks. Lundy had a lacerated left knee with effusion and contused right thigh, with gasoline burns (first degree) of buttocks.

In late October 1955, Mrs. Gillis received a letter informing her that since her son had no known grave, his name would appear on the Ottawa Memorial.

The full court of inquiry with witness statements can be found on microfiche T-12340, starting at image 3038.

LINKS: