November 3, 1918 - April 22, 1943

Douglas Peter Lamont was the son of Daniel Peter Lamont and his wife, Agnes Mable (nee Turnbull) Lamont of Minto, Manitoba, south of Brandon. He had two brothers: Hugh Robert Lamont(LAC 172825, RCAF, Bella Bella, BC), Murray Turnbull Lamont, and three sisters: Helen Margaret Lamont, Gwendolyn Marian Lamont, and Isobel McLaurier Lamont. (His sisters all resided at the same address in Brandon (429 Princess Avenue.) The family attended the United Church.

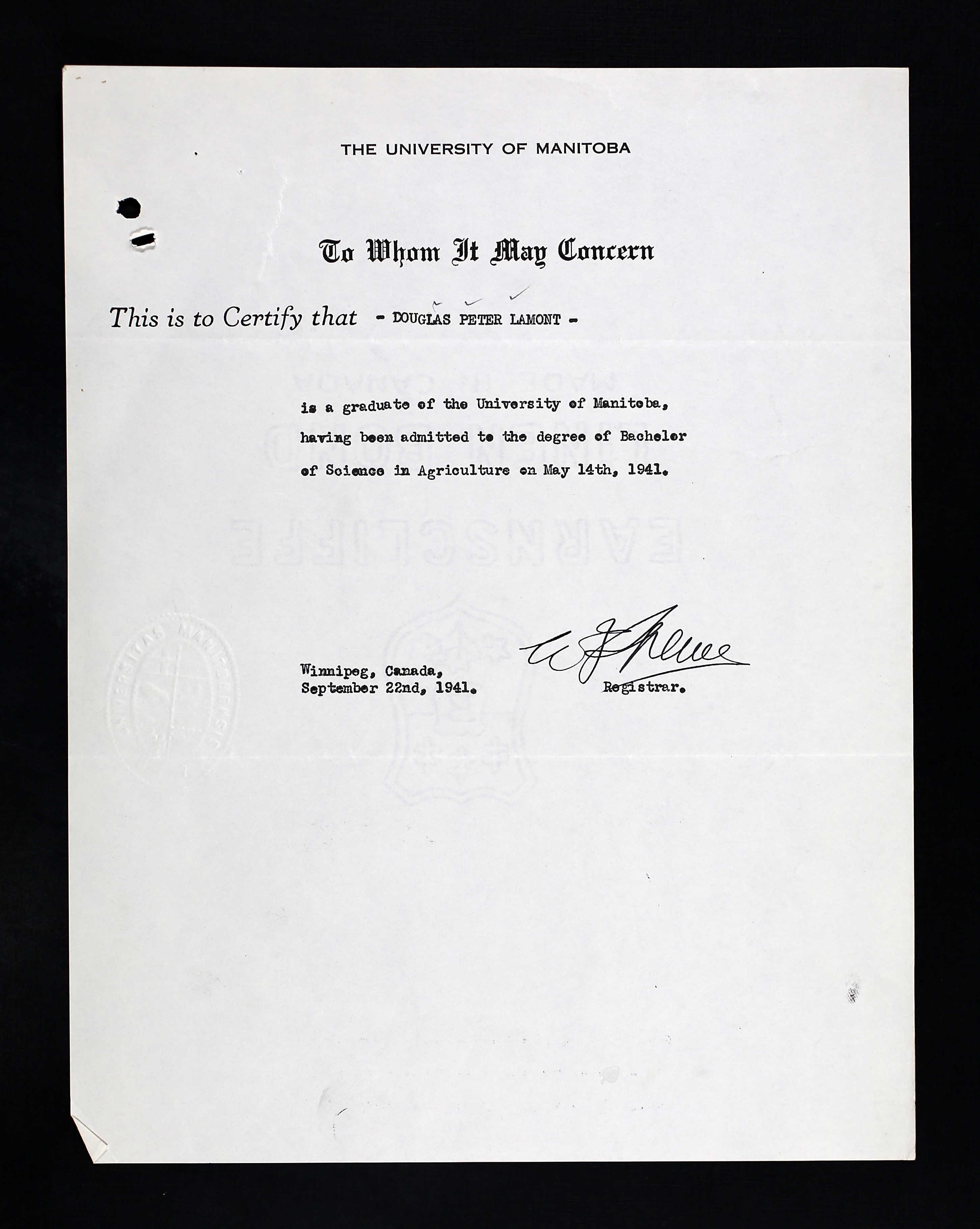

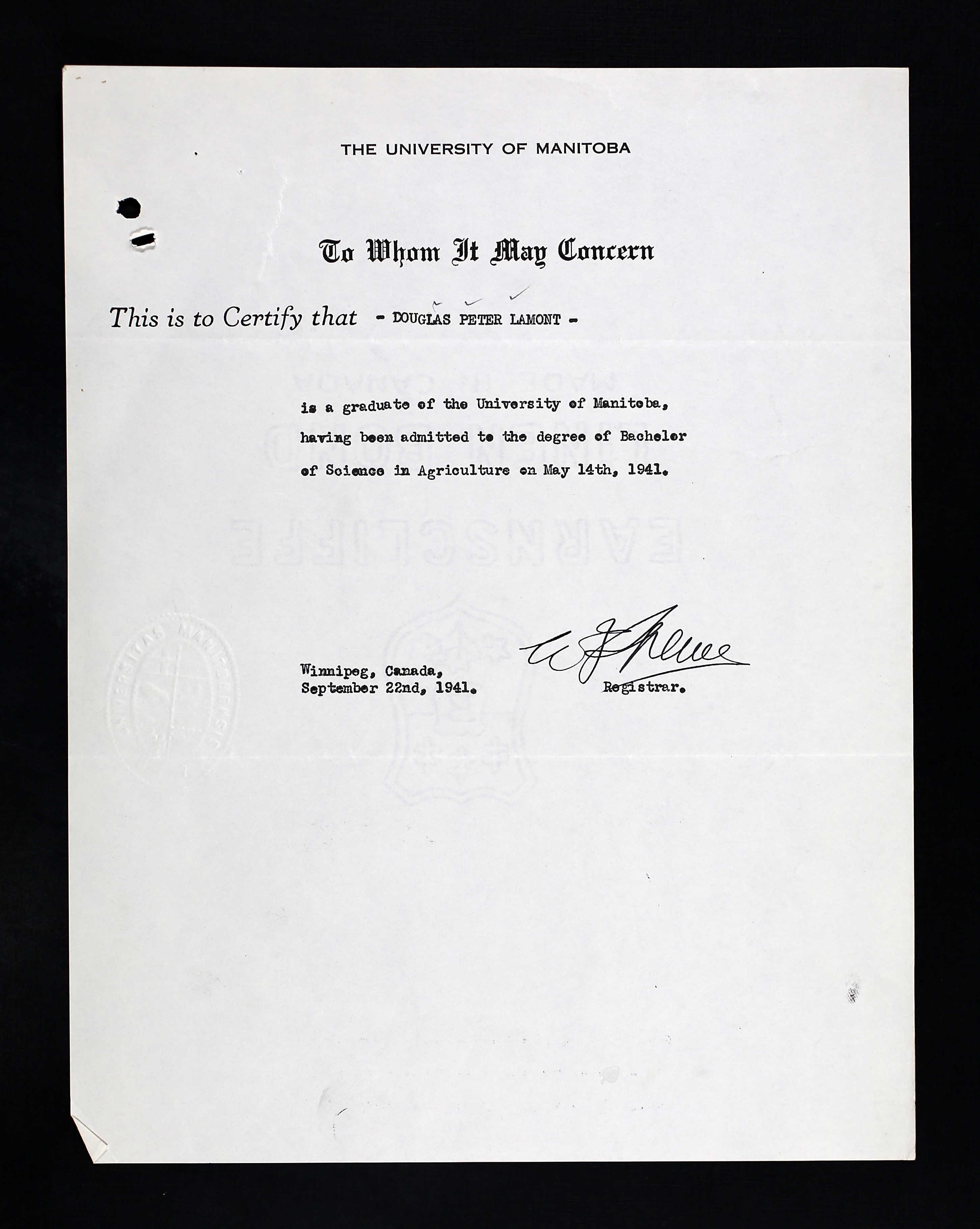

He studied four years at the University of Manitoba receiving a Bachelor of Science in Agriculture, graduating in 1941. He worked as an Agricultural Supervisor at the Experimental Farm in Brandon for the Department of Agriculture. “I have had considerable experience in supervising seeding of airports in cooperation with the Department of Transport.”

He was in debt $100 to the University of Manitoba on the Loan Fund.

Douglas enlisted in Winnipeg on September 23, 1941 wanting flying duties. “Good type. Keen. Alert. And Intelligent.” He was possible commission material. In December 1941, he suffered for ten days with pharyngitis (sore throat).

He liked basketball, swimming, tennis, baseball, and football. His hobby was gas engine mechanics. He stood 5’ 9 ¾” tall, weighed 147 pounds, had a fair complexion, hazel eyes and brown hair. Distinguishing marks included acne on his back and shoulders, plus a mole 3” on the left side of his spine. “Physique: sedentary. Mentality: alert.”

He started his journey through the BCATP on November 20, 1941 at No. 3 Manning Depot, Edmonton, Alberta until he was sent to No. 3 SFTS in Calgary on February 1, 1942.

In late March 1942, he was up in Edmonton at No. 4 ITS until August 1, 1942. “Above average night visual acuity.” In April, 1942: “Under treatment and improving considered fit for aircrew as much as for ground as far as this condition affects.” Possibly, this related to low pressure in chamber 2. He was 38th out of 93 in class with 81%. “Average team sports. Brother wireless airgunner in RCAF. Quite, retiring type. NCO material. Alternative: Air Bomber.”

Then Douglas was sent to No. 5 ETFS, High River, Alberta until September 26, 1942. He was 17th out of 41 in class with 82%. “Above average ground school, average flying ability, weak in airmanship, doesn’t look around enough. Conduct very good.”

He was then sent to No. 10 SFTS, Dauphin, Manitoba until November 17, 1942. “Average student, hardworking, but lacks force. Neat in appearance and attitude good. Thinks slowly.”

Douglas’s training was discontinued and he was sent to Composite Training School (KTS) Trenton, Ontario November 18 until December 4, 1942.

Douglas was sent to No. 7 Bombing and Gunnery School in Paulson, Manitoba December 5, 1942 until February 6, 1943, then to No. 7 Air Observer School in Portage la Prairie, Manitoba until April 3, 1943. “Bombing: Good bomb aimer. Desirable type as aircrew. Has a good grasp of both practical and theory. This airman is suitable and well qualified to attend the special course in advanced bombing. Gunnery: Average gunner. Steady and reliable. Theory average. General: Above average generally. Industrious and co-operative. Should make an excellent air crew member.” 76.4%, 22nd out of 29 in class. He received his commission on March 19, 1943, receiving his Air Bomber’s Badge.

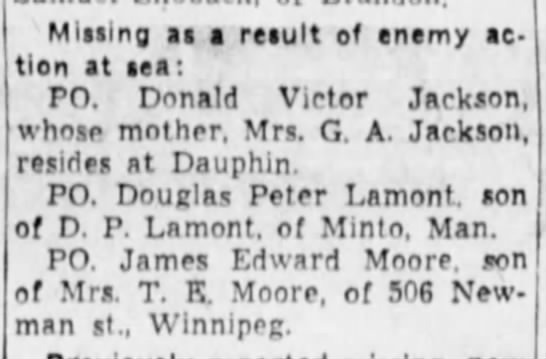

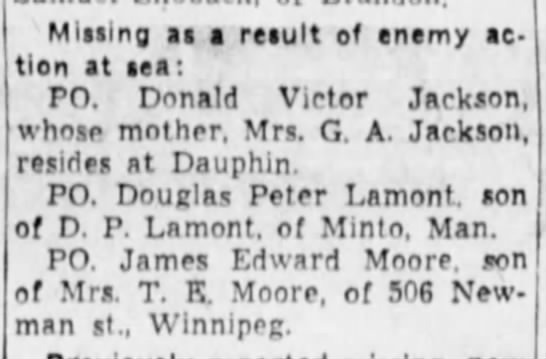

Douglas boarded a train bound for Halifax and Y Depot, where he awaited transport overseas, becoming part of the RAF Trainees’ Pool. Douglas then embarked for Liverpool aboard the Amerika, a British Motor merchant ship. It was torpedoed by U-306 south of Cape Farewell, off Greenland, as the ship was heading to Britain, a straggler in convoy HX-234. Thirty-seven men, all officers in the RCAF, were presumed missing as a result of enemy action at sea, including Douglas; sixteen others were landed at a British port. Forty-two crew members and seven gunners were also amongst those who were lost. The master, Christian Nielsen, 29 crewmembers, eight gunners, and sixteen passengers were picked up by the HMS Asphodel, and landed at Greenock. General cargo, including metal, flour, meat and 200 bags of mail were also lost.

Mr. and Mrs. Lamont received a letter in June 1943 from F/L W. R. Gunn, RCAF Casualties Officer for Chief of the Air Staff. "Since my letter of May 6th, no additional news has been received. Attached is a list of the names and next-of-kin of sixteen Royal Canadian Air Force officers who embarked on the same ship as your son and following enemy action at sea were safely landed in the United Kingdom. The following official statement was made in the House of Commons....’I have been in receipt of communications from a number of members of this house and from people outside with reference to rumours regarding the recent loss of a number of members of the RCAF by the sinking of a ship in the north Atlantic and I desire to make the following statement on the facts. The vessel in question was a ship of British registry of 8,862 tons, designed for peace-time carriage of both passengers and freight, and having a speed of fifteen knots. She carried a crew of 86 and the passenger accommodation consisted of 12 two-berth rooms with bath and 29 other berths, providing cabin accommodations for 53 passengers. She was fitted with lifeboat capacity for 231 and travelled in naval convoy. Under the recently revised regulations agreed to by the United States authorities, the joint United Kingdom and United States shipping board, the Admiralty, the Air Ministry and the Canadian authorities, a vessel of this description travelling in convoy is permitted to embark as crew and passengers a maximum of 75% of the lifeboat capacity. The lifeboat capacity as stated above was 231, 75% of which is 173. Personnel on board consisted of the crew of 86, and RCAF personnel numbering 53, a total of 139, well within the prescribed limits. Because of the superior type of available passenger accommodation, the speed of the ship and the provision of naval convoy, the offer of the entire available space to the RCAF was immediately accepted. Rumours to the effect that this was a slow freighter not suitable for passenger accommodation are, of course, not in accord with the facts. Every precaution was taken to safeguard the lives of these gallant young men. It should be pointed out that on account of the serious shipping shortage every available berth on such ships must be used, and had the space not been taken up by the RCAF officers of the other arms of the services would have been placed on Board. It should also be stated again that the submarine is still the enemy’s most powerful weapon and that the Battle of the Atlantic is not yet won. Any ocean trip today in any part of the world is fraught with danger and I think I may safely say that our record in transporting our soldiers and airmen to the United Kingdom is one of while we may all be proud. No one deplores more than I do the loss of 37 of the finest of our young men who gave their lives for their country as surely as if they had done so in actual combat with the enemy, and I extend my deepest sympathy to their loved ones in their bereavement.’ If further information becomes available, you are to be reassured it will be communicated to you at once. May I again extend to you my sincere sympathy in this time of great anxiety."

In early January 1944, Douglas’s mother received another letter from S/L W. R. Gunn that Douglas would now be presumed dead for official purposes.

In October 1955, a letter addressed to Mr. and Mrs Lamont from W/C W. R. Gunn informing them that Douglas’s name would appear on the Ottawa Memorial, as Douglas had no known grave, expressing sympathy on the loss of her gallant son.